Is a deadlift necessarily a deadlift if you don’t pick the bar up from the floor?

Trick question.

Deadlifting (or not) from the floor depends on the individual’s hip structure, unique biomechanics, and alignment and how they could affect the client’s ability to actually reach the bar on the floor. However, pretty much everyone does pull from the floor, whether they have the requisite mobility to do it or not. This is a problem.

The general thought is that if someone can’t deadlift from the floor without some sort of problem, then:

* They just need to work on their mobility

* Suck it up and be a man

* Hang their head in shame for being an unevolved human being (yes, the internet sucks holy hell because some people actually do talk to one another like this)

Sure, if they “worked on their mobility” and focused on core control, along with learning the positioning and ability to develop tension in that position, some people could see improvements in being able to deadlift from the floor.

But many others won’t.

What’s the big deal?

The set up for a deadlift depends on the individual’s height so that when you get low to grab the bar, you may require anywhere from 115 to 130 degrees of hip flexion. This is also dependent on torso length relative to leg length, as well as whether the individual sets up with a high hip or low hip.

Overall, sufficient hip flexion angle matters a whole lot. In a conventional stance, that angle occurs in an almost entirely sagittal plane alignment, which is also a common zone of hip impingement.

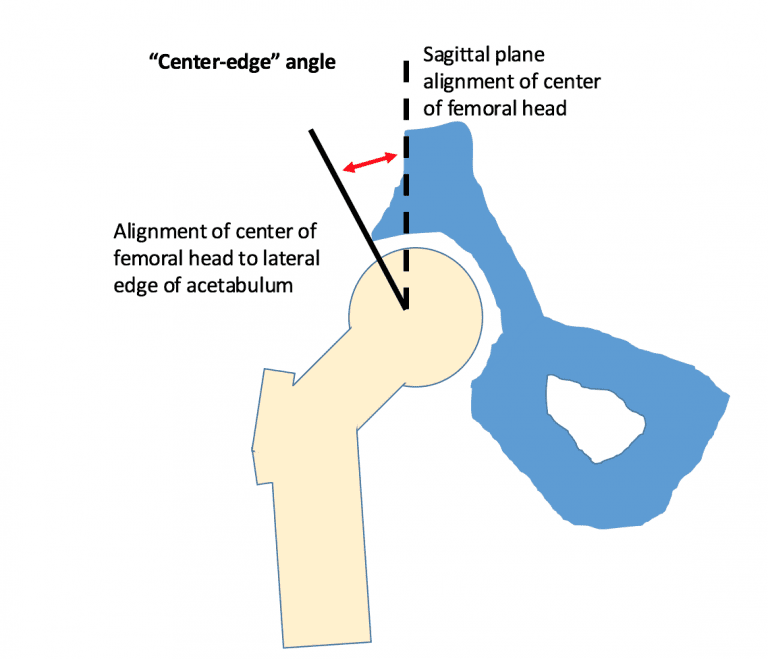

If an individual happens to have more of a retroverted acetabulum that limits movement into deep flexion, past 110 degrees, there’s more of a center edge angle that could predicate bone to bone contact in this position. Compare that to a less center edge angle, which would allow more motion before bone to bone contact occurs.

Free-drawn by Dean Somerset

Because of this potential structural limitation through hip flexion, some people may not be able to get into position to properly pull the weight from the floor without trying to find motion somewhere else. Remember, the great thing about the body is it always finds a way to do the job, even to its own detriment.

Should your client deadlift from the floor if their back rounds?

If the person runs out of hip flexion range of motion, the body can make up the difference by adding in lumbar flexion range. This is a common situation where the low back looks like it’s rounding, or even developing a hinge at one or two vertebral segments. When looking at the low back directly, it looks like wings or fins riding along the spine, or like the spine has a sudden kink at one spot instead of having a smooth bend.

It’s a bad thing to have your back round, right? Not quite, and again, it depends. Bret Contreras wrote an article on how involving upper back rounding was different from low-back rounding, especially for advanced powerlifters. In essence, some rounding of the thoracic spine can boost performance, but it is not a technique that is recommended for beginners.

On the other hand, there are a couple of reasons why rounding the low back on set up could be a bad idea. First, if the low back is flexing to meet the bar, one of two things will happen when you pull the bar off the floor: the low back initiates the first phase of movement to get back to neutral; or it doesn’t and, instead, stays in that position or potentially slips further into flexion.

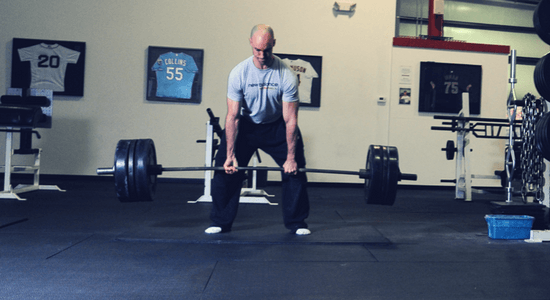

Photo credit: https://bretcontreras.com/how-to-increase-your-deadlift/

If a low back is initiating movement against load while in flexion, it takes over the responsibility of the prime movers in the hips, making the lift slower or weaker than it should be. It also makes the low back do considerably more work than it ever should do, which can predispose it to potential tissue failure, especially if in the presence of fatigue.

If the spine stays flexed throughout the movement or drifts further into flexion, the vertebral body and disc are now exposed to a magnitude of shear force 10 times greater than if they were in more of a “neutral” position (which I know is a contentious term to anatomy geeks). Shear force can cause some damage to discs, vertebral ligaments, and other connective tissue. Plus, they tend to decrease activity of the lumbar erector spinae when in a forward flexed position.

In other words, a stretched muscle under load won’t be able to flex as hard as a shortened muscle under the same load. Over time, the risk of the muscle not being able to hold the joint together goes up significantly as the magnitude of that force increases and the reactive moment of those muscles decreases.

The million-dollar question: Should someone who doesn’t have the hip anatomy to grab the bar without compensating with low back flexion even worry about pulling a bar off the floor?

Consider the plates that are used by two people of varying heights. Most plates are typically a set height, meaning that if you’re 5 or 7 feet tall, you have to bend down to the same position. The person who is 5-foot has to pull from a position that’s almost at their knee, whereas the 7-foot person has to essentially be tying their shoes at the start position.

No one would tell a 7-foot basketball player to deadlift from the floor since it’s such an aggressive hip position and doesn’t warrant the risk for their ability. But why do we figure a 5-foot-10 accountant named Dave should have to pull from the floor versus from an elevated position?

3 safer and better alternatives to pulling from the floor

In all honesty, there are only two sports or activities that would require your client to deadlift from the floor: powerlifting and Olympic lifting.

In both of those sports, the weight starts on the floor and you have to lift from that position, regardless of your body’s dimensions, height, hip anatomy, etc. For any other sport, activity, training goal, or lifestyle, deadlifting from the floor may not be necessary and could actually be counterproductive to the relative risk to benefit ratio for the individual.

For many people, a floor pull is actually a deficit pull.

Let’s say your client is in a situation where he rounds his low back when he goes to grab the bar in a conventional stance. His feet remain under his hips, but he still wants to deadlift off the floor. There are a couple of potential options you could work with:

1. Take a slightly modified sumo stance approach

This means setting up with a foot width stance that is slightly wider than shoulder width. For many, around the width of the grip you would use for bench press is fine too. Then your client can grab the bar inside the feet and pull from that position. In many cases, this more lateral stance tends to allow a more free hip motion through flexion, but also has the added benefit of shortening the lever length of the thigh acting on the low back.

2. Use a trap bar

You could also use a trap bar, which has a higher handle height and situates the bar more easily underneath your client’s center of gravity and over the base of support compared to a traditional barbell.

Occasionally, because we all have some level of asymmetry in our pelvic structure, it may even warrant turning one of your client’s toes out further than the other, or even having one foot set up behind the other.

3. Set the weights higher

If either of the above options are still not enough to counter the lack of hip mobility to grab the bar without flexing the spine, set the weights up on risers on the floor, either with some pads or other plates. You could also simply use a squat rack to do a rack pull from an elevated position, which would still allow the individual to train the movement within their abilities. Rack pulls would still allow clients to overload that could develop a training effect similar to pulling from the floor, but without exposing the spine to unnecessary and potentially detrimental forces.

Bottom line, don’t get hung up on having to do an exercise a specific way that may not work well with your client’s specific body anatomy, abilities, or limitations. Sometimes a slightly reduced range of motion or an altered stance can give your client the same training effect you’re looking for, but without the same risks. Understand that there are many different paths that can lead in the same direction.

This blog post originally appeared on deansomerset.com. It has been reposted here on The PTDC with permission.