My athlete dropped his barbell after three reps.

“I feel like I just ran a marathon,” he said, gasping.

“This is the worst. It’s been a month since I’ve been able to climb the stairs to my apartment without stopping to take a break.”

Sound familiar?

We trainers have seen lots of gasping clients recently as the COVID-19 pandemic recedes.

Some were sidelined by the illness itself, like my client, but plenty of others merely stayed out of the gym and aren’t as fit as they used to be.

There’s a surprising way to help your clients come back stronger from the pandemic:

Breathing training.

That’s right—applying training principles to the breathing muscles.

Adding breathing training to almost anyone’s workout program is a great idea, whether they were sick or not.

I’ll tell you why.

Breathing training can boost athletic performance—and results.

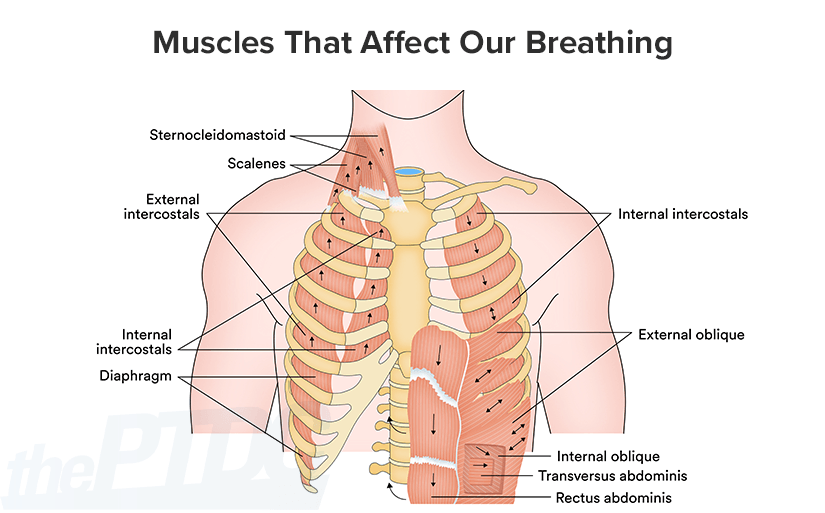

Did you know there are about 10 pounds of muscle that affect our breathing? Those muscles (like any muscle) should be trained.

Breathing training works for everyone, including:

- Athletes competing in barbell sports

- Triathletes

- Anyone who wants to be healthier and happier

Many of our clients spend much of the day trapped in a shallow breathing pattern. That’s part of modern life—too much sitting, too much worrying.

Quick, shallow breathing tells our brain (via the vagus nerve) that we are being threatened and might have to run.

Slow, deep breaths convince our brain and body to keep chillin’.

Ever see golfers or basketball players take a deep, calming breath before swinging or taking a free throw? Same thing.

Our breathing rate affects the body in multiple ways:

- Stress hormone levels like cortisol and adrenaline

- Heart rate and blood pressure

- Posture and mechanical patterns

I’m betting few of your clients know how to breathe properly, or how to train their bodies to breathe better.

That’s because even something as fundamental as breathing needs to be taught, just as a basic movement pattern like a squat requires instruction.

I would argue that just five minutes of breathing training out of every workout will give your clients more bang for their buck out of the whole session, as well as the recovery afterward.

Health benefits of breathing training

Countless studies show that breathing training can help with a host of health issues, including asthma, anxiety, and depression, and “long COVID” symptoms.

Sitting at a desk or watching TV or staring at your phone can contribute to poor posture (usually slouching and forward-head position). This can lead to tight muscles in the anterior chain and weakened and lengthened muscles across the upper back. All of this may limit pulmonary function.

Better breathing helps offset all of that.

There’s also a clear link between breathing patterns and anxiety, studies show. (So you can literally breathe a sigh of relief—go ahead, I’ll wait.)

I was reminded of the importance of breathing training when I read about the English National Opera’s educational “Breathe” program for sufferers of long COVID symptoms (like crushing fatigue, brain fog, breathlessness, and anxiety).

The program was based on principles used by opera singers to produce and project sound. It helped long-COVID patients breathe calmly, soothe anxiety, and slowly expand their damaged lung capacity.

Nine out of 10 participants said the program had a “positive” or “strong positive” effect on their recovery.

I play tuba and bass trombone, so I know something about breathing mechanics.

Musicians and singers know that projecting sound requires good mechanics. And without a powerful but relaxed breathing pattern, tension and fatigue will kick in, affecting tone and projection.

So we musicians need to build strength and work capacity, the same way an athlete does.

Which muscles does breathing training strengthen?

Everyone thinks of the diaphragm as the primary breathing muscle, which it is.

But other primary breathing muscles include the intercostals, obliques, and transverse abdominis.

Secondary muscles used in breathing include the pectoralis group, trapezius, and sternocleidomastoid.

In most people, all that muscle is lying nearly dormant as we spend hours every day sitting on our butts.

Those muscles can and should be trained to make the most of our lung capacity.

One problem: We can’t feel a burn in our breathing muscles, so you may think the breathing muscles don’t tire. Instead, we get a global fatigue that seems psychological, affecting our focus, willpower, and motivation.

Ever tried to get through a tough workout but felt like your arms and legs were too heavy? That can be traced to a phenomenon called the “respiratory metaboreflex.”

When your diaphragm and other breathing muscles start to fatigue, your body wants to send them more oxygen, so it restricts blood flow to the arms and legs.

And that’s what makes your arms and legs feel heavy. Makes sense, but it’s not a good feeling!

The good news is that breathing patterns are trainable. You can make those breathing muscles stronger and more efficient, so the rest of the body won’t be deprived of oxygen.

Result: more productive workouts.

Like every other muscle group, breathing muscles need to be trained specifically to grow stronger. A foundation in breathing training is important whatever the goal of your clients:

- General health

- Fat loss

- Strength

- Endurance

The two most effective breathing workouts (and how to teach them)

Diaphragmatic breathing

At the beginning of the workout, have your client lie supine on the floor, with one hand on their belly and one hand on their chest.

Inhale for two counts—the first count should lift up the hand on their belly, the second count should lift up the hand on the chest. Then exhale with a sigh—no specific length, just be relaxed. (Note: For this exercise, you can inhale and exhale through the nose or mouth, whichever feels more comfortable.)

Repeat for 10 to 15 breaths (or set a timer for two minutes). Your client might feel a little dizzy, so warn them of this possibility ahead of time.

Proceed with your workout, and when you’re done, go to box breathing.

Box breathing

Have your client sit upright in a comfortable position and inhale through the nose for a count of four, hold for a count of four, exhale through the nose for a count of four, and hold for a count of four. (That’s the “box.” Imagine drawing a square—up, across, down, back to the starting point).

Start clients with 4 sets of 4 box breaths, which takes about four minutes.

Box breathing slows the respiratory rate and gets clients used to breathing less, thus reducing adrenaline and cortisol.

Advanced breathing exercises

When you (or your client) have established a good breathing pattern, you can increase strength by “loading” the breathing pattern. Using a musical instrument, or the voice, or the techniques in this video (the pop, double pop, and "let it leak") can all help with that.

Here’s another cool trick from Stuart McGill, from his book Ultimate Back Strength and Performance:

Perform a high-intensity cardio exercise (such as riding an assault bike, kettlebell swings, or rope slams) for about a minute—enough to get your heart pounding. At the one-minute mark, drop down into a side plank. All of the muscles that would normally assist with breathing are busy in that position, forcing the diaphragm to pick up all the work. You build “the shield” through core stiffness, and behind the shield the diaphragm becomes a pump.

Those basics are plenty for clients in the general population.

Now let’s talk about breathing training for athletic goals.

Breathing training for athletes: Apply the principle of specificity

Strength athletes need to dial in proper breathing and bracing for maximal strength:

- Practice 360-degree breathing—a full, deep breath where the whole torso expands in all directions.

- Manage intra-abdominal pressure, which stabilizes the spine and allows the athlete to lift more weight.

- Create a strong abdominal “cannister”—bracing or contracting ALL of the core musculature, and then forcing the diaphragm down with a deep breath, producing intra-abdominal pressure.

For the endurance athlete, increasing efficiency and going longer without fatigue are key. Building strength in the breathing muscles can decrease the respiratory metaboreflex, so there’ll be less fatigue in the working arms and legs.

Consider what happened during your last cardio workout. You probably started huffing and puffing a little bit, right?

If you consciously slowed and deepened your breathing, you’d use more of your lung capacity, increasing the oxygen supply to your working muscles.

You can increase the work capacity of the respiratory muscles by controlling the speed and depth of your breath during lower-intensity cardio.

Try doing one long, slower workout every week breathing through your nose. Or breathe through a straw in your mouth for five minutes during your warmup.

Giving our clients control over their breath and their bodies is a critical piece of teaching resilience—something we want for all our clients regardless of their goals.

Remember, good breathing is a skill, and developing it with practice and intent can improve our clients’ quality of life in a myriad of ways.