Physical activity is a natural part of being human, and exercise is an essential part of a healthy lifestyle.

And as everyone involved in fitness knows, training is also an invaluable tool for shaping and sculpting the body. Progressive resistance training is especially effective when it comes to body recomposition, as it increases lean mass and helps you build a muscular frame and good-looking physique.

But what about those folks who want to shed fat? Is it effective to exercise to lose weight? Conventional wisdom says yes, and on a superficial level it makes sense that expending more energy can help you get into the pants you've been keeping around since your lean days.

Does Exercise for Weight Loss Hold up in the Real World?

The idea that exercise "burns off the fat" is so ingrained in most people's belief system that we just accept it as true, and selling gym memberships and personal training on the idea that the best way is to exercise to lose weight has become a simple task.

Also, since it's easy to find an isolated study that seems to show significant exercise-induced weight loss, the average gym goer rarely questions the link between exercise and weight loss. If the actual workout results don't stack up to the preconceived notions -- as they often don't in terms of exercise for weight loss -- the conclusion is that it's something wrong with the training program or the general effort in the gym, not with the underlying premise of the training.

However, physical activity hasn't always been synonymous with weight loss. It wasn't until the 1960s that researchers, such as the French-American nutritionist Jean Mayer, really began extolling the virtues of exercise in the treatment of overweight and obesity.

Despite the many limitations and weaknesses of the early studies on exercise and fat loss, the idea that expending more energy helps you shed the pounds was so easy to believe that the mantra "eat less, move more" started to gain foothold as weight loss advice 101.

Physical Activity Levels Throughout History

In evolutionary terms clearly the average human energy expenditure has declined dramatically. It's no doubt that the majority of people living in the world today would benefit from being more active, but we can't extrapolate the mismatch between energy expenditure in the lean Paleolithic man and energy expenditure in the overweight modern human to mean that exercise is the way to go for leanness.

Also, the fact that several non-westernized cultures, such as the Kitavans on the Island of Kitava and the Hadza of Northern Tanzania, are lean and healthy even though they aren't especially active suggests that we don't necessarily have to exercise to be lean (1).

Furthermore, while it's often believed that we are less active today than in any other part of human evolution, statistics show that physical activity expenditure has not declined over the same period that obesity rates have increased dramatically (2). Although this doesn't tell us that much about the connection between exercise and weight loss, it does make it clear that inactivity, at least in itself, is not the primary cause of the obesity epidemic.

Does Pouring More Energy Out of the System Transfer Into Fat Loss?

Weight training promotes muscle growth and strength development as an adaptive response to exercise, and it's sometimes assumed that fat loss is an adaptive response to aerobic exercise since a leaner body could lead to better performance in aerobic activities. When talking about exercise-induced energy expenditure, I'm not just talking about energy output during training, but also the elevated energy expenditure that occurs in the hours (and days) after a workout.

Everyone with a basic understanding of thermodynamics agrees that creating an imbalanced energy equation is necessary to either gain or lose weight, which means that you either have to increase energy expenditure, decrease energy intake, or both if you want to get rid of the excess belly fat. Since we know that the human body isn't a passive vehicle that simply comes along for the ride, this doesn't necessarily mean that telling people to move more is good weight loss advice.

Of course, if you restrict your caloric intake to a specific amount of calories each day (as dieting bodybuilders and folks on low-calorie diets do), increasing your energy expenditure through exercise will naturally help you lose more fat. However, that isn't what we're talking about here. Someone who's already very lean and want to shed more fat (e.g., down to single digits of body fat for male), generally has to consciously restrict calories to lose weight.

Conscious calorie restriction can also play a role for those who are overweight and obese, but studies show that simply going on a calorie restricted diet is rarely effective in the long-term. This is because you're fighting your body's hard-wired mechanisms for regulating fat storage.

Yes, energy expenditure has to increase and/or energy intake has to decrease if you want to lose weight, but this should happen naturally as a result of the diet you're eating and your lifestyle, not by chronically starving yourself.

So I'm not discussing the 200-pound fitness competitor who goes on a calorie restricted diet to get ready for the stage. Naturally, this guy will shed more fat if he expends more energy through exercising, while at the same time keeps his energy intake the same.

I'm talking about those folks who are interested in long-term weight loss and aren't going to starve themselves forever. Because this is where the important question lies: Can we simply pour more energy out of the system (our body) to lose weight, or will the system kick-start mechanisms that make us compensate for the increased energy output to maintain what it considers to be an equilibrium?

Controlling for Confounding Variables

What happens when people start working out? They generally get more interested in health and nutrition and often change their diet, sleeping patterns, etc. This isn't a universal behaviour, but it's a very common one. Most of us have probably heard about that guy who lost a lot of weight when he started exercising, but was it really the exercise in itself that triggered the weight loss? Perhaps he made other lifestyle changes that affected fat regulation, or perhaps this person simply was one of those people who respond great to exercise.

However, some folks also respond in the opposite way in the sense that they reward themselves for the efforts in the gym by eating more crap (most people tend to overestimate the amount of calories burned during exercise) and being less active during the rest of the day. The fact is that we can't really draw any universal conclusions from these types of anecdotal reports.

These types of confounding variables are one of the primary reasons why it's so hard to carry out well-controlled studies on exercise for weight loss. Unless it's a metabolic ward study, participants are typically given a training program to follow for a certain number of weeks and then sent home.

Even though participants are supervised along the way, it's very difficult to control for various lifestyle factors that can affect the results. That's why it's generally easier to do a study where subjects are instructed to exercise while at the same time eat a calorie restricted diet.

However, the problem with these studies is that they don't really tell us much about the effectiveness of exercise on its own. Naturally, a higher energy expenditure will help boost fat loss if you eat a calorie restricted diet, because we're eliminating compensatory mechanisms as increased food intake.

What Does the Science Really Say About Exercise for Weight Loss?

There are hundreds of studies investigating the effects of exercise for weight loss, so let's narrow the scope by looking at comprehensive reviews, meta-analyses, and high-quality randomized-controlled trials.

Meta-analyses are often considered the strongest possible evidence since they combine results from several different studies, and there's no doubt that high quality meta-analyses and systematic reviews provide invaluable information.

However, it's important to note that these types of statistical analyses also have their limitations. it's important that you figure out how to quickly analyze fitness research. They can only be as good as the studies they are based on, and one problem with "lumping" several trials together is that the strength and weaknesses of each study sometimes get lost. However, meta-analyses and systematic reviews provide a good overview of the current data (Skip this list if you're not interested in the hard facts).

Let's begin by looking at some of the data from the 1980s and 1990s. In 1997, a meta-analysis of the past 25 years of weight loss research found that a 15-week diet or diet plus exercise program resulted in the same weight loss after 15 weeks (11 kg) (3).

While total weight loss was the same, diet plus exercise intervention resulted in a slightly higher fat loss. Weight loss due to exercise alone was 2.9 kg. This meta-analysis focused on the obese population. Two other meta-analysis (4,5) found that weight loss through exercise alone is lower (1-2 kg) in non-obese subjects.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis looked at the randomized controlled trials done on isolated aerobic exercise (no dietary intervention) and weight loss. The review composed of 14 trials involving 1847 overweight or obese patients shows that isolated aerobic exercise only results in an average weight loss of 1.6 kg after six months, and an additional 6 months of training didn't result in any additional weight reduction (6).

"Evidence indicates that even when the exercise is supervised and closely monitored, there's variability in weight change, both in the direction and magnitude" (7). While some people find that exercise on its own is somewhat effective for weight loss, others actually gain weight because they end up compensating by eating more food.

One of the most recent reviews (2014) on the role of exercise and physical activity in weight loss and maintenance concludes the following: "Based on the present literature, unless the overall volume of aerobic ET is very high, clinically significant weight loss is unlikely to occur. Also, ET also has an important role in weight regain after initial weight loss.

Overall, aerobic ET programs consistent with public health recommendations may promote up to modest weight loss (~2 kg), however the weight loss on an individual level is highly heterogeneous. Clinicians should educate their patients on reasonable expectations of weight loss based on their physical activity program and emphasize that numerous health benefits occur from PA programs in the absence of weight loss (8) ."

Another recent review (2013) had the following to say about high-intensity exercise versus moderate-intensity exercise for weight loss: "... in the literature on overweight or obese people, there is little conclusive evidence for more favorable effects with high-intensity training than with continuous moderate-intensity exercise on body weight or fat mass loss (9)."

Since the purpose of resistance exercise usually isn't to lose weight, it's no surprise that aerobic exercise seems to be more effective for visceral fat loss (10). While isolated resistance training like weight lifting isn't associated with any significant reduction in fat mass, an increase in muscle mass may lead to better metabolic control and increased basal metabolic rate, and resistance exercise is therefore often recommended in the prevention and management of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other metabolic disorders.

Clearly if we look at the evidence as a whole, neither aerobic nor anaerobic exercise is very effective for fat loss (for the vast majority of people). This goes for both HIIT and regular cardio training. However, both aerobic and anaerobic exercise have a positive effect on insulin resistance, appetite control, blood pressure, etc. Some studies also show that some people respond to exercise by losing a "significant" amount of weight (11, 12).

Although these mixed results to a degree stem from a true individual variability, I personally believe that confounding variables, such as sleep and diet, can help explain some of the difference between participants in these studies. Regardless of how well researchers try to control for these variables, it's very difficult to stay on top of these things when participants aren't confined to a controlled environment.

These results seem to go against what most people believe in when it comes to exercise and weight loss. While research does support the idea that some people lose quite a bit of fat from exercising more, the average fat loss is modest at best. So, what is going on here? Why doesn't the elevated energy expenditure both during and after exercise transfer into fat loss?

The Body's Compensatory Responses to Exercise for Weight Loss

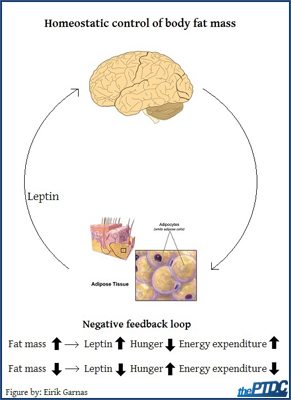

It's long been known that the amount of body fat we carry is homeostatically regulated (13-16). If food intake goes down and/or exercise-induced energy expenditure goes up, the hypothalamus triggers processes (e.g., interest in food, decreased body heat production) to restore energy reserves. Obesity researchers often refer to this "defended" level of body fat as the fat mass set point (more like a range).

So while few people will argue against the fact that we have to decrease energy intake and/or decrease energy expenditure to lose weight, we also have to take into account that the body has its own mechanisms for regulating fat storage.

Like so many dieters have experienced, if we exercise more and restrict calories in an attempt to lose weight, energy expenditure per unit lean mass declines and we will be hungry and tired.

Compensatory mechanisms to exercise, such as increased food intake and/or less activity during the rest of the day, are the primary reason why the energy you burn off during exercise doesn't necessarily transfer into permanent weight loss.

Exercise, Metabolic Health, and Food Reward

To really be able to lose weight, we have to understand how to work with our body and design a fat loss plan that helps us take control of the homeostatic system that controls fat storage on a long-term basis. This means that we have to address the causes of overeating, poor leptin sensitivity, and elevated fat mass set point.

Environmental inputs and lifestyle have a significant effect on these processes, and diet is by far the most important factor. But what about exercise? The general belief that exercise could make you lose weight because it increases energy expenditure doesn't necessarily hold up very well since body fat levels are regulated by the brain.

However, exercise has also been shown to decrease inflammation and improve metabolic health -- most notably leptin and insulin sensitivity -- and these benefits probably explain why some people find that exercise is effective for weight loss.

Furthermore, exercise has a significant effect on food reward regions in the brain, but the effects seem to be highly individual, with some people experiencing an increased interest in food following exercise, while others display a reduced responsiveness to food cues (17).

As the brain is the control center for regulating energy expenditure and energy intake, these varying effects on the food-reward network could largely explain why some people respond to exercise by eating more, while others eat less. If it was just about the calories, one would expect everyone to lose the same amount of fat from exercise, given the same level of exercise-induced energy expenditure.

Wrap Up

I find that the science on exercise for weight loss is fairly consistent with my own experiences as a personal trainer. Since the idea that exercise leads to weight loss is so ingrained in most people's belief system, many gym goers who hire a personal trainer simply think they'll lose weight if they start exercising more. Getting clients to understand that increasing their activity levels generally doesn't lead to much in terms of fat loss can therefore be a difficult task.

Believe me, I wish exercise was very effective for weight loss, as it would've made my job as a trainer/coach a lot easier. However, I acknowledge that although exercise comes with a wide spectrum of benefits, the evidence as a whole doesn't show that it helps you lose a lot of weight.

Does this mean that exercise is a waste of time for people who are overweight and obese? No. Regular physical is an essential part of a healthy lifestyle, and there's no doubt that the modern sedentary lifestyle is one of the primary causes of the so-called diseases of civilization. Also, while exercise isn't the number one priority when it comes to losing weight, regular physical activity seems to be important in the prevention of obesity, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. It's also important to remember that regular exercise allows you to eat more food without gaining fat, and for those foodies out there, this could be a win in itself.

In conclusion, the scientific literature as a whole shows that isolated (no dietary intervention) exercise for weight loss usually isn't very effective. This suggests that most people compensate for the exercise-induced energy expenditure by eating more and/or being less active during the rest of the day.

However, a minority find that exercise on its own is very effective for weight loss, and this probably has to do with the effects on metabolic health and food-reward systems in the brain. Don't exercise to lose weight but instead to build a strong, fit, and healthy body.

Further Reading

Help! My Clients Won't Follow Nutrition Advice - Jonathan Goodman

47 Random Personal Trainer Tips - Jonathan Goodman

How Much Should You Charge for Personal Training? - Brett Jarman

References

- http://www.staffanlindeberg.com/TheKitavaStudy.html.

- Westerterp KR, Speakman JR. Physical activity energy expenditure has not declined since the 1980s and matches energy expenditures of wild mammals. International journal of obesity (2005). 2008;32(8):1256-63.

- Miller WC, Koceja DM, Hamilton EJ. A meta-analysis of the past 25 years of weight loss research using diet, exercise or diet plus exercise intervention. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1997;21(10):941-7.

- Epstein LH, Wing RR. Aerobic exercise and weight. Addictive behaviors. 1980;5(4):371-88.

- Ballor DL, Keesey RE. A meta-analysis of the factors affecting exercise-induced changes in body mass, fat mass and fat-free mass in males and females. International journal of obesity. 1991;15(11):717-26.

- Thorogood A, Mottillo S, Shimony A, Filion KB, Joseph L, Genest J, et al. Isolated aerobic exercise and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American journal of medicine. 2011;124(8):747-55.

- King NA, Horner K, Hills AP, Byrne NM, Wood RE, Bryant E, et al. Exercise, appetite and weight management: understanding the compensatory responses in eating behaviour and how they contribute to variability in exercise-induced weight loss. British journal of sports medicine. 2012;46(5):315-22.

- Swift DL, Johannsen NM, Lavie CJ, Earnest CP, Church TS. The role of exercise and physical activity in weight loss and maintenance. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2014;56(4):441-7.

- De Feo P. Is high-intensity exercise better than moderate-intensity exercise for weight loss? Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases : NMCD. 2013;23(11):1037-42.

- Slentz CA, Bateman LA, Willis LH, Shields AT, Tanner CJ, Piner LW, et al. Effects of aerobic vs. resistance training on visceral and liver fat stores, liver enzymes, and insulin resistance by HOMA in overweight adults from STRRIDE AT/RT. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;301(5):E1033-9.

- King NA, Caudwell PP, Hopkins M, Stubbs JR, Naslund E, Blundell JE. Dual-process action of exercise on appetite control: increase in orexigenic drive but improvement in meal-induced satiety. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009;90(4):921-7.

- Donnelly JE, Honas JJ, Smith BK, Mayo MS, Gibson CA, Sullivan DK, et al. Aerobic exercise alone results in clinically significant weight loss for men and women: midwest exercise trial 2. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2013;21(3):E219-28.

- Guyenet SJ, Schwartz MW. Clinical review: Regulation of food intake, energy balance, and body fat mass: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of obesity. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2012;97(3):745-55.

- Myers MG, Cowley MA, Munzberg H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annual review of physiology. 2008;70:537-56.

- Lutter M, Nestler EJ. Homeostatic and hedonic signals interact in the regulation of food intake. The Journal of nutrition. 2009;139(3):629-32.

- Friedman JM. A tale of two hormones. Nature medicine. 2010;16(10):1100-6.

- http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/04/16/does-exercise-make-you-overeat/.