One time a client who wanted to lose weight broke down and cried right before our training session. It was jarring, but in time I’ve learned that this is not uncommon.

Clients count on our expertise to help them lose weight, if that’s their goal, but we must also realize that by the time they come to us they’re battered and worn from myriad setbacks and are desperate for hope. Understand that, based on their past experiences with failure, they’d rather not try, because potentially stumbling again (even if it is a tiny remote chance) is too psychologically painful, as this study in Diabetes Care suggests.

Perhaps you have good intentions and have read all of the cutting-edge tactics on helping a client get the results they want, but how can you be sure you’re not hurting the client further -- psychologically, emotionally, or maybe physically?

That’s what I want to go over in this article, friends. Specifically, I will outline:

- How some weight loss recommendations can do more harm than good

- The myth of a “damaged metabolism”

- The right approach to weight loss that the best coaches implement

Here we go!

“ feel a shame that they are failures, and failure itself is such a powerful thing that it eats away at a person. How do you fuel positive change through guilt and shame and feeling like a failure?” - Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, MD

One of the most important steps we can take toward facilitating a client’s success is to (respectfully) address misinformation, correctly assess her sticking points, and steer her toward behaviors that support weight loss (and keeping it off long-term).

We know that to achieve weight loss we must induce a calorie deficit, which can be done by restricting calories and following an exercise program. Both are integral parts of a weight loss plan, but both can also be taken to the extreme and leave clients miserable, physiologically and emotionally, and cause them to fall off the wagon. An “extreme” plan might include 60 minutes of cardio, six or seven days per week, and lifting five times per week.

If you make such recommendations, you’re being an irresponsible coach, hands down. In fact, you could be doing possible damage to your client.

It’s Not JUST a Calorie Deficit

While it is true that to lose weight a person must be in a caloric deficit, we know that weight doesn’t magically go away so effortlessly and predictably in the real world.

Weight loss already is not easy, but combine a difficult process with the plethora of misinformation or incomplete information and promises of “quick and easy” fixes, and you have a recipe to set people up for failure.

Jordan Syatt, a personal trainer whose impressive client roster includes influencers like Gary Vaynerchuk, says that poorly prescribed fat loss plans are ones that:

“Don't offer any support outside of nutrition. As in there's no accountability. No motivation. No check-ins or asking, "hey, how are you feeling?" Nutrition (and strength) coaching is far more than just dishing out numbers and programs. It's about getting to know your client and how to not only motivate them, but help them learn how to motivate themselves.”

There’s a sweet spot for caloric restriction that can nudge weight loss, but still avoid possible physiological and emotional damage to the client. Studies show that while exercise is important, weight loss from exercise alone is modest and must be supplemented with a sound diet that leaves the client in a deficit.

But the amount of physical activity needed to actually maintain weight loss is high and individualized. For example, individuals in the National Weight Control Registry who have maintained weight loss have activity levels that are equivalent to walking approximately 28 miles per week. That’s a ton of steps!

In other words, you need to understand two important things:

- Your client needs high levels of physical activity.

- But your client’s high levels of activity do not have to be vigorous.

That means your client does not need to do hours and hours of slogging away on the elliptical or treadmill each day. Rather, they’d likely benefit from moderately intense cardiovascular activity for 30 minutes three times per week, with increased walking throughout the day.

Example: Suggest that your client take a 10-minute walk during lunch breaks and a 20-30-minute walk after dinner. Either suggestion is easier to maintain compared to 60 minutes of pounding the stairmaster every day of the week.

Is It Possible to Harm Someone’s Metabolism?

You’ve probably heard horror stories of clients whose metabolism was completely wrecked from following low-calorie diets and programs that involved superhuman levels of activity.

It’s not hard to see why people can be misinformed. Precision Nutrition published an excellent article, written by Brian St. Pierre, RD, on this very topic. As he wrote in the article, the equation for changes in body composition is:

Changes in body stores = energy in - energy out

The above equation holds true for everyone, but there are a lot of other factors that must be considered, such as:

- Sex hormone levels

- Macronutrient intake

- Exercise style

- Age

- Medication

- Genetic predisposition

The “energy in” component is simply more complicated than most of us think. The number on the menu or food label isn’t necessarily accurate and can be off by as much as 25 percent. To further muddy the waters, the amount of calories our individual body can absorb is different from the number or label on the menu too.

Thus, it’s tough to accurately measure how many calories we’re really eating. Can you unequivocally proclaim that you ate exactly 500 calories just because McDonald’s website says the Big Mac is 500 calories? No, you can’t take those numbers at face value.

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with the calorie-in-calorie-out equation.

Plugging the “right numbers” into the equation is challenging, but the point I’m really trying to highlight is that attributing a lack of weight loss progress to “metabolic damage” is merely convenient and misleading. The truth is, creating a negative energy balance is the only way an individual will lose weight. Dr. Spencer Nadolsky, a board certified family and obesity medicine physician, states:

“Low-calorie diets are the main treatment for obesity. We can't get around this. They don't damage metabolism. The only way to lose weight is to be on a lower energy diet. It doesn't have to be very low (800 or less), but has to be lower than what they are on now. If done properly, it is fine and actually evidence-based.”

Hear that? Low-calorie diets are fine and effective for fat loss. In fact, you can be aggressive, but knowing when to not be aggressive is key, Dr. Nadolsky says. For example, if your client has a binge-eating disorder, an aggressively low-calorie diet might not be ideal nor sustainable. Plus, low-calorie diets can become problematic if your client has a history of rebound. St. Pierre explains why in his article:

“Because of adaptation your body undergoes in response to fat loss, energy out for those who have lost significant weight will always be lower for people who were always lean...Unfortunately, because of this adaptive response, someone who has dieted down will often require 5-15% fewer calories per day to maintain the weight and physical activity level than someone who has always been that weight.”

So you would be messing up your client if you set her up with a low-calorie diet that causes her weight to constantly fluctuate. Additionally, Syatt shares that the TRUE marker of a good weight loss diet isn’t whether you cram crazy amounts of protein or leafy greens or superfoods (whatever that means) into it, although those can be beneficial.

A good weight loss diet is sustainable. Syatt says:

“I've seen some coaches put normal "average joe" clients on 800 calories per day for months at a time, which clearly doesn't work because no one can stick to it so they end up binging and gaining weight.”

Yikes. Since you’re reading this article, you know that there’s a better way, of course.

Focus on Behaviors, Not the Meal and Exercise Plan

“Understanding the who, what, when, where, and why behind each client. It's not just about physiology. It's psychology. And the more you understand the emotional side of why people make certain choices regarding their health, the better you and your clients will do.” - Jordan Syatt

There are always certain keystone behaviors that must be reinforced in order for successful fat loss to occur, which is why I prefer a flexible approach.

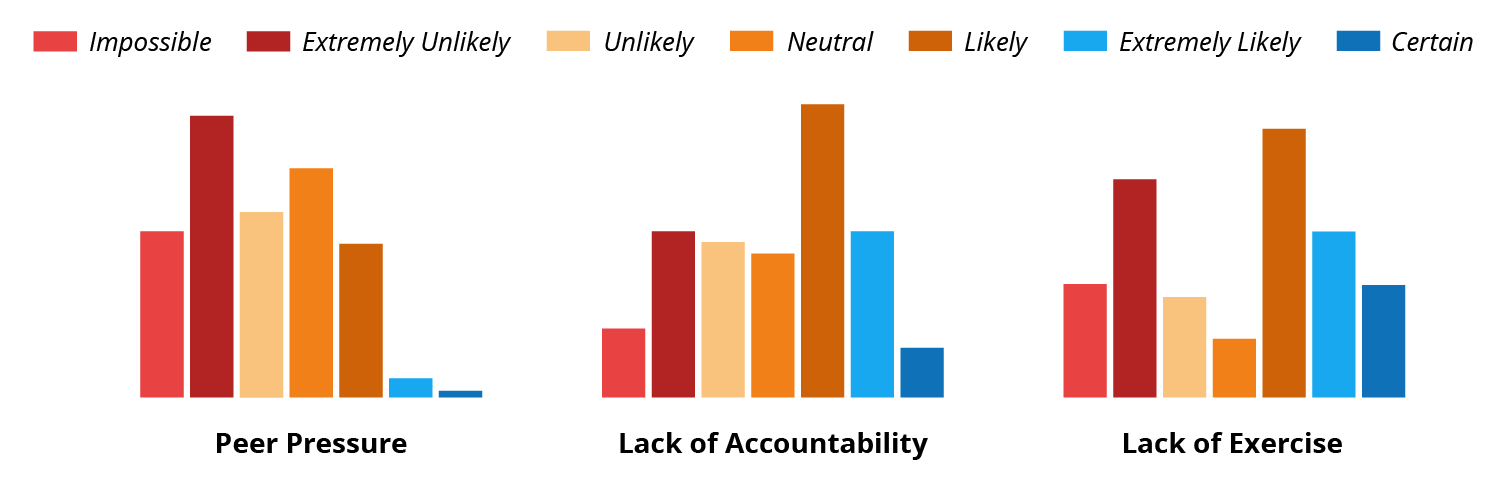

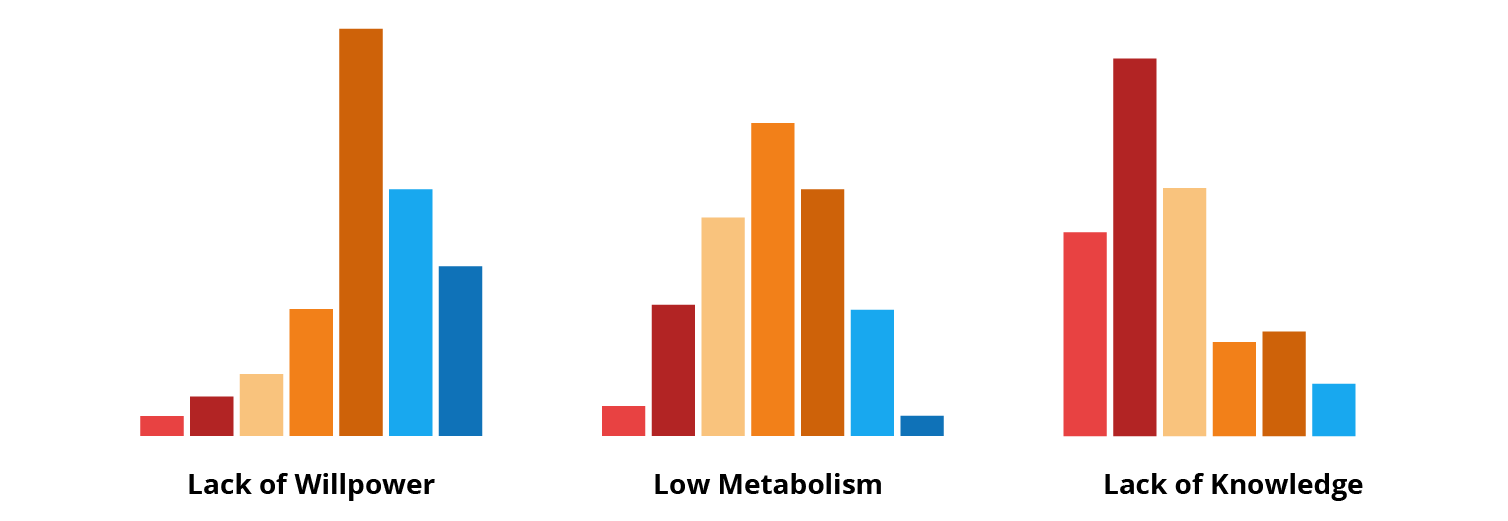

In a recent research experiment, several colleagues and I interviewed over 200 participants with weight loss goals. We examined each of their perceived weight loss barriers. Based on our initial results, it was clear that an individualized approach is necessary (see graphs below). For example, look at the variation in responses for lack of accountability. One person may need to address this barrier, whereas accountability may be unimportant for another.

When designing an individualized plan, you should first understand the machinery behind motivation and its relation to behavioral change, and have a system in place to assess behaviors that facilitate caloric restriction.

When designing an individualized plan, you should first understand the machinery behind motivation and its relation to behavioral change, and have a system in place to assess behaviors that facilitate caloric restriction.

What does this mean for you?

You need to establish an environment where a client has competence and autonomy. Here’s what I mean:

- Competence:

Competence is providing your client with the skills and tools necessary for behavioral change. For example, a client may express interest in learning resistance training, so you coach the client on correct exercise technique to help them feel competent. You want to avoid overly challenging him and help him gain mastery in whatever behavior he decides to pursue. - Autonomy:

Autonomy is allowing your clients to have personal choice in adopting health behaviors because they would be more likely to comply when they personally value a behavior. For example, if a person has no interest in cutting back soda consumption, don’t force this behavior upon her. It will likely threaten her sense of autonomy and may backfire. To support autonomy, give the client a personal choice and help when she explores her barriers to her own weight loss. To increase personal motivation, help her link chosen behaviors to life values. For example, find out what the client really cares about in life (i.e. being a good parent or going on adventures) and help them create a link between those -- what they are doing in the gym and what they are eating -- to these life values.

The next step is to think about a system that can assess their needs and be flexible based on the client’s needs and desires.

Using a Survey to Help Give Your Clients Autonomy and Competence

One way to reinforce autonomy and competence is to survey your clients and identify those behaviors which clients want to start improving first. You can easily make surveys using free tools like Survey Monkey or simple forms from Google (like these).

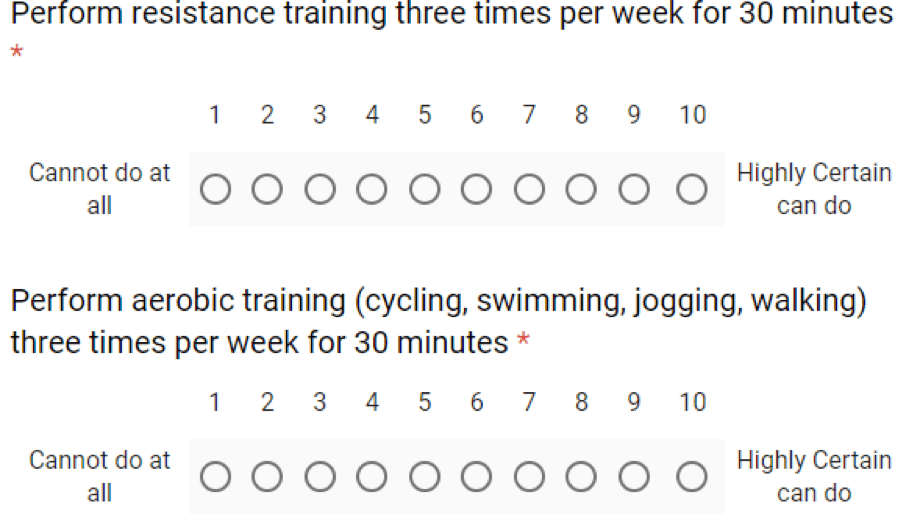

It is important to address behaviors that need to be adopted in order for the client to be successful, which you can find out from surveying them. I use a linear scale (0-10 or 0% to 100%) that measures their confidence toward performing certain behaviors. (You can reference the National Weight Control Registry for ideas on some of these behaviors.)

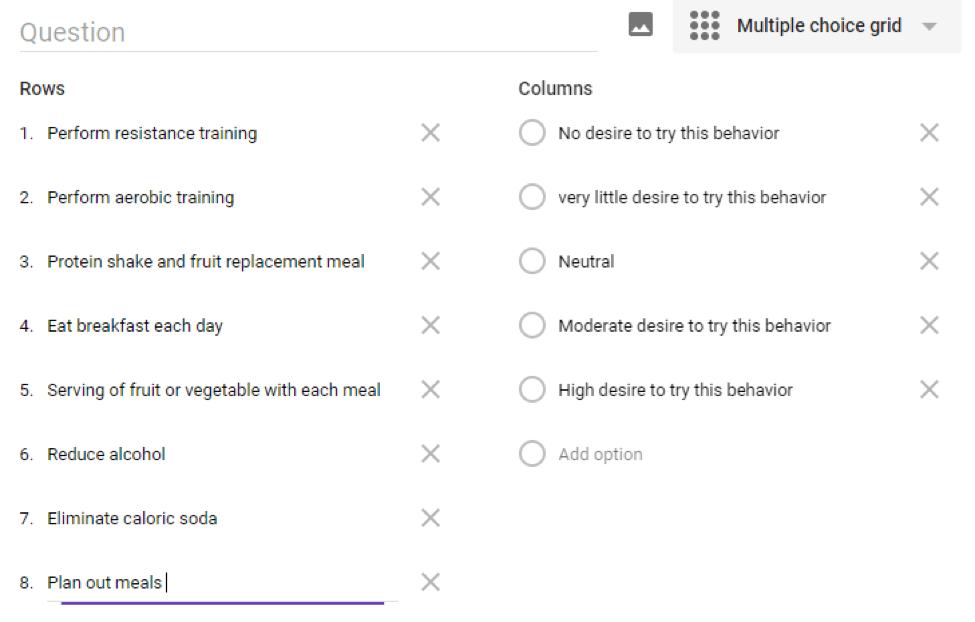

Confidence is important, but so is autonomy. A client may be very confident in their abilities to do a behavior, but has no desire to actually do the behavior. So let the client pick the behavior they do want to work on. Use the multiple-choice grid option for this.

Once a client has filled out a survey like this, you can have a rough idea of what behaviors they are motivated to perform. If a client is motivated (high confidence and wants to do the behavior) to reduce soda intake, you can move into a planning phase with them.

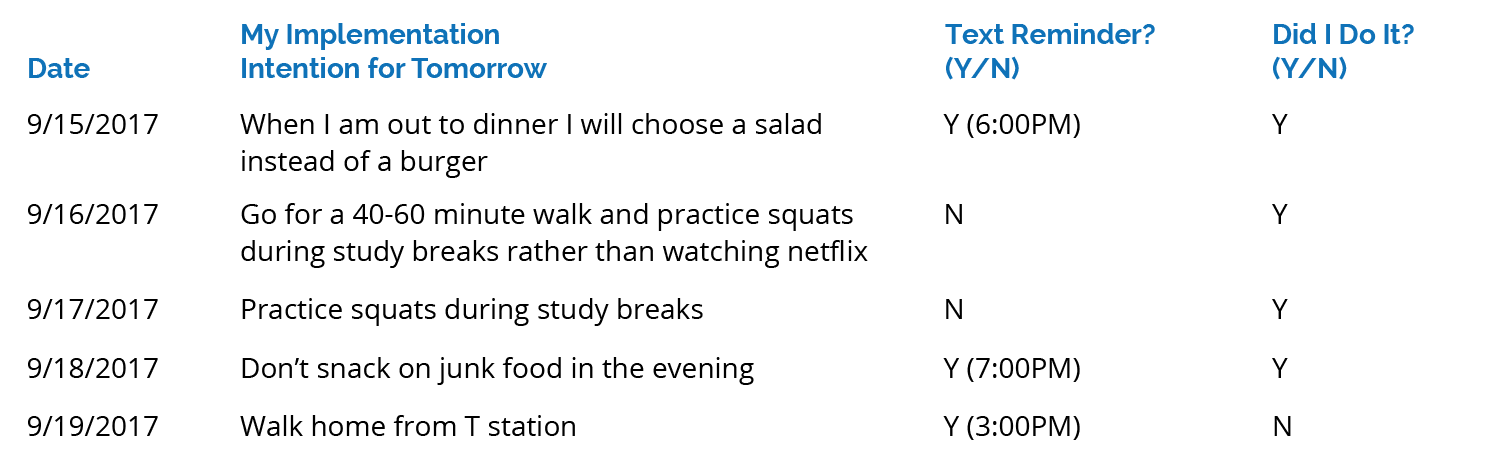

This planning phase might take the form of an implementation intention, which dictates when, where, and how a behavior might occur. For this person, the plan might be:

“When I am going grocery shopping, I will buy the diet coke instead of the regular coke” or “When I am going grocery shopping, I will buy seltzer water instead of soda”

A trainer can set up a shared spreadsheet with a client such as the one below where they can type in their daily health intentions. The below screenshot is an example:

To help set up automatic reminders to continue these motivated behaviors, I use the automatic text messaging service ohdontforget.com. It’s not free, but can be worth it when your clients start seeing results and improved confidence (and refer you to more of their friends).

Bottom-line: Extreme deficits and exercise plans can give your clients quick wins, but may ultimately burn them when they inevitably fall off. Your and your client’s best chance of success must involve a form of physical activity that they can sustain as well as appropriate dietary changes that they won’t hate doing as well.

Whatever plan you give your client should allow them to feel competent and autonomous because doing so will contribute to long-term motivation and a better chance at sticking to these changes for life.