TODAY WAS THE DAY.

No more bands, no more iso holds, no more eccentrics.

It was time for the real thing.

She approached the rack with a little zest (not entirely sure what song she had just listened to), stepped her way up to the pull-up bar, and grabbed hold for the ride.

Following a big breath and brace, she pulled as hard as she could and glided right up, pure euphoria spreading across her face as her chin passed the bar.

I thought she was going to perform a back flip off the rack. Instead she hopped down and gave me a huge high-five—she had just crushed her first pull-up.

As trainers, it's important to first ask the right questions and then move our clients down the path towards their goals. Many times, one of those goals will be to either do a single pull-up or just crush pull-ups period.

While the pull-up might look simple, it's anything but that. There are many intricacies to be aware of if you hope to help your clients how to master pull-ups. This article will walk you through everything from clearing someone to do a pull-up, to the biomechanics behind it, to the execution, programming, cueing and everything in-between.

The Basics

To get the most out of pull-ups for your clients, you need to have a good understanding of what they are and what you're hoping to accomplish.

For starters, the pull-up family can be broken down into three separate hand positions:

1. Chin-Up

An example of a chin up. Note the supinated grip.

2. Neutral Grip Pull-Up

An example of a neutral grip pull-up.

3. Pull-Up

An example of a conventional pull-up

Each hand position changes the movement because you're manipulating the position of the shoulder throughout the range of motion. For example, a chin-up is biasing external rotation while a pull-up is biasing more internal rotation. For someone with a history of shoulder pain, these small differences can make a big difference.

Let me point out the importance of abs. Everyone knows pull-ups can build tremendous upper body strength, size, and power, but few people respect the role abs play in this movement. In particular, you need to view pull-ups as an epic tug of war between the lats and abs (especially obliques).

To quickly review the main role of abdominal muscles, let's turn to Shirley Sahrmann:

"The most important aspect of abdominal muscle performance is obtaining the control that is necessary to (1) appropriately stabilize the spine, (2) maintain optimal alignment and movement relationships between the pelvis and the spine, and (3) prevent excessive stress and compensatory motions of the pelvis during movements of the extremities."

So a well-executed pull-up is working on all three of these qualities. As clients pull themselves up, their abs must fire and counteract the pull of the lats or else they'll fly straight into large amounts of extension. We'll be talking more about this in the technique section, so let's move on to screening your clients for pull-ups.

Clearing Someone

Like all other exercises, pull-ups are neither good nor bad until you place them within a specific context. At some point during the on-boarding process with a new client, you'll put them through an assessment that should tell you a lot about how that person moves and what he or she wants to achieve over the next 3-6 months. Let's just say pull-ups recruit lats big time!

The lats can overpower the entire system and push someone into a chronic extension pattern. Again, extension isn't inherently good or bad as long as someone has the capacity to control it. But far too often, those who have done tons of pull-ups over their lifetime can't oppose their lats.

For this reason, these individuals live in extension all day, and pull-ups aren't a good option for them up front. They need to spend some time solidifying the "center" of their body, and then gradually introduce pull-ups over time once they can control/oppose their lats.

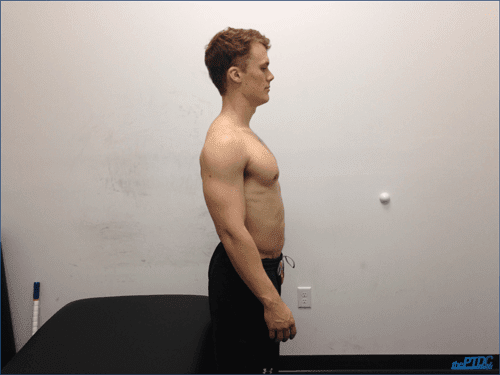

Here are a few basic red flags to be on the lookout for:

Arms behind midline

What it looks like when the arm is beyond the midline

Bilateral rib flare

An example of a bilateral rib flare. (Photo credit: http://www.billhartman.net.

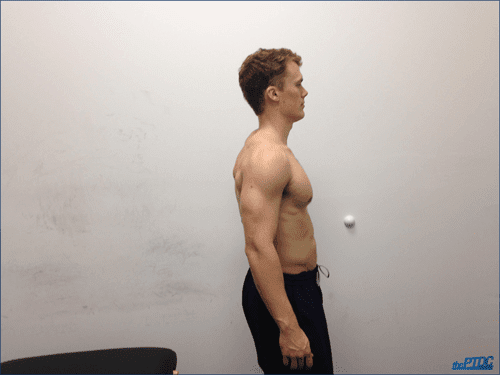

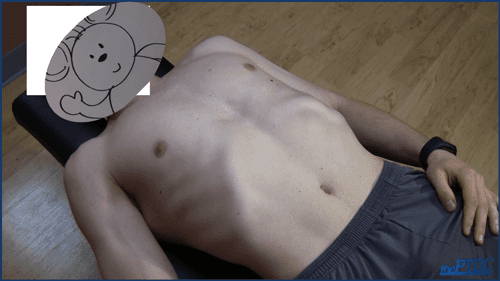

Deep back/Gross extension

Note: It's difficult to see my back in this picture, but notice how "open" I am anteriorly (ribs up and pelvis forward).

An example of deep back / gross extension

Limited IR Everywhere

Don't have a picture for this, but if you test someone who has limited internal rotation pretty much everywhere on their body, then they are very extended.

Limited Should Flexion

When performing this test, make sure you're holding down their ribs. If you allow their ribs to flare, you aren't testing true shoulder flexion.

An example of limited shoulder flexion

I'm assuming your primary concern with training is overall health. If you're with a high-level sprinter, powerlifter, strongman, football player etc, whose primary concern is performance, then the conversation will look much different.

When you train high-level performers or advanced personal training clients there's always going to be a tradeoff between health and performance because they're vastly different. For a general fitness client, however, it tends to be more about overall health, so beware of dominant lats.

There's obviously much more to the assessment and clearing process. But thinking in terms of lats versus the entire system (and we don't want lats dominating the system), should help you make sure your clients are doing the right exercise at the right time.

Technique

Common Flaws

There are many ways to get a pull-up wrong, but here are 4 major flaws you need to keep an eye out for:

1. Driving into extension

The most common flaw is that people lose core integrity and fly into extension (ribs flare and pelvis rolls forward).

Maintaining good position is particularly difficult with the pull-up because of how big a role the lats play. The lat has distal attachments on the spinous processes of T7-T12, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and the last 3-4 ribs. Thus, it's in a perfect position to push someone into extension.

To counteract this pull or stiffness, you need to fire, among other things, your obliques, rectus and transverse abdominis. In other words, you need to use your abs.

Although this may not seem like a big deal, the position of your lumbopelvic region has wide reaching effects. If that's off, it will make you more likely to commit the other mistakes below.

Remember, extension is necessary at times for power development, but this isn't one of those times. You need to convince your clients that a pull-up is really a moving plank where they're working on anti-extension.

2.Reaching with chin

This goes for just about everything: keep a double chin. There's no exercise where your client's head, chin etc. should be driving forward and up.

3. Humeral anterior glide and Scapular anterior tilt

To keep your client's shoulders strong and healthy, it's all about maintaining position of the humeral head in the socket. When you pull your elbows past your body or round your shoulders forward, you're not accomplishing that goal.

Instead of getting good scapulohumeral rhythm, your client is cranking on their anterior shoulder and managing to avoid using the muscles this exercise is intended to use.

4. Flailing

This one speaks for itself. Just don't allow it.

How To Do It Right

When it comes to helping your clients crush a pull-up, it all starts with the set up.

Here's how to do it:

Now that they're set up, here's what they need to focus on. And you can tell them this verbatim, but I'd recommend dropping the anatomy jargon:

While maintaining a strong lumbopelvic position (aka bracing and maintaining core integrity), initiate the movement by pulling your shoulder blades toward their respective opposite butt cheeks (put your shoulder blades in your back pockets).

Once the scaps are set, think about pulling your elbows straight down to your hips and pulling your chin over the bar. At the top (with chin packed, shoulders back, and "neutral" lumbar positioning) reverse and lower yourself to the bottom.

In case you missed any of what we've gone over this far, here's a quick video tying it all together:

Where to Start

Just getting the ball rolling on pull-ups is often the hardest part, so here are three ways to help your clients experience some success in the beginning:

1. Isometric Holds

Isometric exercise increases absolute strength and works within regional specificity"”simply meaning it trains the angle at which you hold plus some (anywhere up to 15 degrees in both directions).

It's a good place for people who can't perform the full range of motion but can do holds at different points throughout the range. As they get strong at one joint angle they often gain the ability to transition to other angles, and thus, progress is made.

I'd recommend starting at the top and working your way down doing five 6 second holds separated by 10 seconds of rest for one set, and then perform anywhere from 5-10 sets.

2.Eccentrics

To quote Verkoshanksky and Siff:

"It's known that eccentric exercise tends to produce greater and more rapid increases in muscle strength and hypertrophy than concentric exercise."

For someone struggling to perform a full pull-up, that sounds like a good option to me. Have your client get up on the bar and lower as slowly as possible. They'll build strength and muscle mass that'll eventually help them do the real thing, and you'll look like a genius.

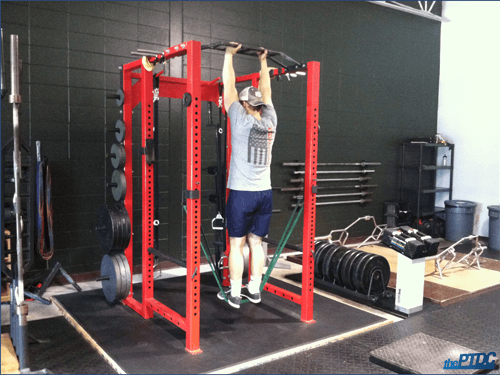

3. Band Assisted Pull-Ups

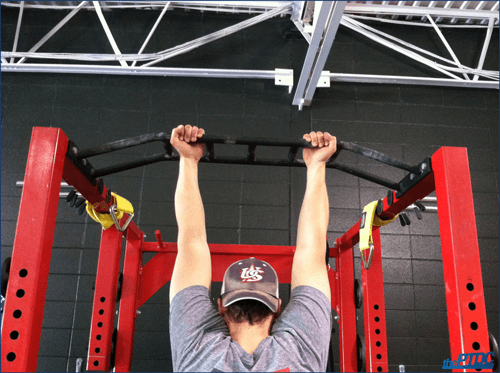

Option 1 (preferred): Band on J-hooks

With the band on j-hooks

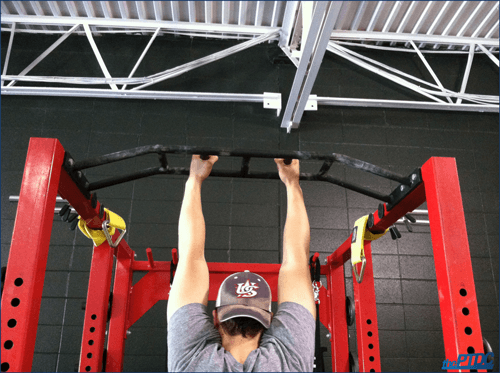

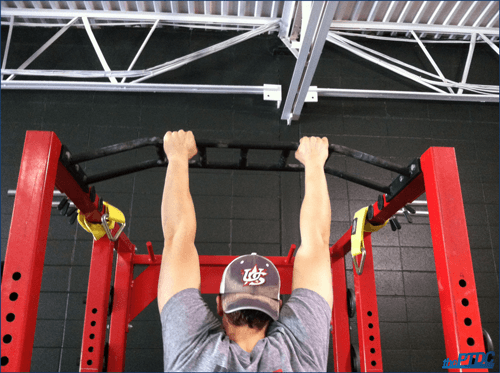

Option 2: Band on bar

With the band on the bar

No matter how much you play with the first two options, this is the moneymaker. Your clients eventually want to be able to perform the movement in its entirety, so they have to practice that way. It's called specificity.

Your nervous system has to learn how to appropriately coordinate the actions of all the different muscles, and the only way to accomplish that is with practice.

Start off with however much band assistance they need, and slowly begin to taper off as they progress from week to week. Eventually the band will disappear and they'll be doing real pull-ups like a boss.

Where to Go

On those rare occasions that you get a stud from day one who already dominates normal pull-ups, you'll need a way to challenge the movement beyond its normal demands or you run the risk of that person getting bored and leaving you for another trainer.

Here are 4 easy ways to raise the bar and keep the challenge fresh:

1. Add weight

The easiest way to make anything more difficult is to add weight to it. Hang weight off a belt, have them hold it between their feet, really whatever goes. Just add some weight and do work.

2. Play with the tempo

Don't overlook the wonderful world of tempo training. Isometric and eccentric training carry benefits specific to themselves, so why not mix concentric, isometric, and eccentric style training to really up the ante?

For example, instead of having your client just pull himself or herself up and down, you can have them pull-up as fast as they can, hold at the top for 3 seconds, and then lower themselves on a 5 count. The combinations are limitless, so play around and use tempo to your advantage.

Here's a cool pull-up challenge to throw at your more advanced clients who are feeling a little ambitious:

Do a pull-up. Hold an isometric at the top for 3 seconds.

Do 2 pull-ups. Hold an isometric at the top of the second rep for 3 seconds.

Do 3 pull-ups. Hold an isometric at the top of the third rep for 3 seconds...

And so on. Continue this cycle and see how many reps they can do before dropping.

3. Change the position of their feet

The most obvious example here is the dreaded L pull-up: have your clients hold their feet out in front of them at 90 degrees (making an L) and then do pull-ups without losing the hold (what's up abs):

You could always play with having one leg up for a few reps and then switching to the other. Again, your imagination is the only thing holding you back.

4. Hand position

Recall from earlier the three different styles of pull-ups: pull-up (palms facing away from you), chin-up (palms facing you), and neutral grip (palms facing each other).

Although it may not seem like a big deal, changing your hand position changes the demand of the movement. For example, you get greater recruitment of the biceps and pec major during the chin up, and greater recruitment of the lower trap during the pull-up.

Either way, the hand position is an easy way to change the movement.

I hope this gives you a good idea of how to challenge your clients moving forward. You can change any one of the four variables mentioned above, or even get fancy and start changing multiple items with something like a tempo L pull-up with 25 pounds hanging off you.

Wrapping Up

The benefits of pull-ups are tremendous when implemented correctly. My biggest recommendation, however, is to spend the time on the front end clearing people to do them:

How do they move?

Are they stuck in extension?

What are their goals?

The last thing you want to do is throw something at your client that's going to exacerbate an existing problem. View the pull-up as a higher-level strength movement that your clients have to earn the right to perform. Once they have the pieces in place to oppose their lats, and then go get after it and have some fun.

References

1 Sahrmann, Shirley. "Abdominal Muscles." Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis: Mosby, 2002. 69.

2 Verkhoshansky, Yuri, and Mel Siff. "Isometric Training." Supertraining. 6th ed. Rome, Italy: Verkhoshansky, 2009. 223-29.

3 Verkhoshansky, Yuri, and Mel Siff. "Eccentric Training." Supertraining. 6th ed. Rome, Italy: Verkhoshansky, 2009. 230-231.

4 Youdas, James W., Collier L. Amundson, Kyle S. Cicero, Justin J. Hahn, David T. Harezlak, and John H. Hollman. "Surface Electromyographic Activation Patterns and Elbow Joint Motion During a Pull-Up, Chin-Up, or Perfect-Pullupâ„¢ Rotational Exercise." Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 24.12 (2010): 3404-414.