Knee pain plays cruel tricks on your clients. If they enjoy exercise, it punishes them for trying to stay active. If they hate exercise, it gives them an excuse not to move more. A client who wants to lose weight knows the extra pounds are contributing to his knee pain, but the knee pain makes it harder to do the physical activity he needs.

And this is the cruelest of them all: Following the wrong workout program when you have bad knees will absolutely make them worse.

So let’s talk about knee pain: what causes it, how to avoid making it worse, and, most important, the exercises and stretches to help your clients feel better and move more.

* What if a movement hurts your knees?

* The best exercises for knee pain

Step 1: Soft-tissue work

Step 2: Ankle mobility drills

Step 3: Hip-dominant exercises

Step 4: Deloaded knee-dominant exercises

Why knee pain happens

I could write an entire article about the causes of knee pain. So to narrow it down, we’ll focus on chronic knee pain.

If your client’s knee pain is related to a specific injury—a strained ligament, torn meniscus, or damage to the kneecap itself—I wouldn’t use any of these strategies unless the client has been evaluated by a professional, and the doctor or physical therapist recommended them for rehab.

Chronic knee pain usually begins with wear and tear, which could be linked to any or all of these:

· Age

· Weight

· Arthritis

· Poor running or lifting mechanics

· Poor or unbalanced muscle strength

· Lack of mobility in the ankle joints

· Old injuries

But before you can address these issues, you have to avoid making the pain worse.

What if a movement hurts your knees?

Your client’s first goal is to reduce or eliminate anything that triggers knee pain. In other words, if it hurts, stop doing it.

Easy enough if we’re talking about a specific exercise, like squats or lunges. Or if the client is a runner whose running clearly makes the pain worse.

But what if the pain occurs when walking, climbing stairs, or getting up and down from a chair? You need to ask your client questions like these.

“When do you feel knee pain?”

· Morning: If your client’s knees are worst in the morning, but get better once she starts moving, it’s typically because of arthritis. Have your client try some knee extensions upon waking, while sitting on the edge of the bed. That should help her feel better faster.

· Midday: My guess would be that the pain is work-related—too much sitting or repetitive movement. You’ll need more information before you can figure out a way to change things up.

· Evening: This is usually a combination of poor muscle strength and poor movement patterns, putting unnecessary stress on the knee joints. You can address all of it with the exercises and stretches you’ll see in a moment.

· Going up stairs: I know it sounds ridiculous to talk about technique—who doesn’t know how to walk up stairs?—but you’d be amazed how much time I’ve spent teaching people how to do it properly. In almost every case, the pain goes away when we alter their technique.

· After sitting for a while: It’s almost always ergonomics—where they sit and how they sit. First I’ll try to improve their posture. If that doesn’t help, I’ll look at the work station and see if they can change the setup.

· After standing for a while: Start with footwear. Shoes without arch support, for example, make it easier for someone’s ankles to roll inward, with the knees following their lead. (I’ll explain in more detail in the next section.) Standing on a hard surface can also make the knees feel like they’ve been hit by hammers.

“Where do you feel knee pain?”

· Inside (medial): It could be a sign of structural damage to the meniscus or a ligament, either of which should be diagnosed by a clinician. Or it could be a problem with the kneecap’s position. Tightness in the iliotibial band, the thick connective tissue on the outside of the leg, can pull the kneecap outward, putting stress on the structures designed to protect the medial side.

· Outside (lateral): It’s often a sign of iliotibial band syndrome, which is different from the tightness I just described. I see it a lot with runners and cyclists. Their repetitive knee flexion and extension causes the IT band to rub against the lateral condyle, the part of the femur that widens to form the knee joint.

· Over the kneecap: Most of the time, it’s caused by a tight patellar tendon, weak quadriceps, faulty movement mechanics, or some combination. All the strategies below should help.

· Behind the kneecap: The culprit could be bursitis (inflammation of one of the dozen or so fluid-filled sacs within the knee joint) or chondromalacia patella (arthritis on the back of the kneecap). In the latter case, the smooth cartilage on the back of the bone wears away, and instead of gliding over the femur, it starts to drag. It’s like rubbing two pieces of sandpaper together.

The best exercises for bad knees

Step 1: Soft-tissue work

The knee is kind of like Hodor: Even though it’s the body’s largest joint, it’s often picked on by smaller joints like the hip and ankle.

I’ll address the ankle in more detail below. First, though, you need to work out the kinks in three typically problematic areas for clients who have knee pain: calves, quads, and IT band.

One big note about foam rolling:

With most exercises, we tell our clients to stop if they feel pain. But with soft-tissue mobilization, the more it hurts, the more they need to do it. They’ll sometimes see stars when they hit a sensitive spot. Again, that’s a sign they need to do more, not less.

You’ll also see in the videos below that I like to foam roll one leg at a time. You can’t hit the entire muscle you’re targeting if you work both simultaneously.

Calf

The gastrocnemius, the larger calf muscle, crosses the knee joint, so it has some impact on knee motion. Have the client rotate her leg to work over the entire muscle—not just the meaty part in the middle, but also the sides, which is where you’re most likely to find those sensitive spots. When she hits one, have her focus on it, even though it hurts.

Quads

Again, rotate the leg to hit all parts of the muscle while stopping to work on any painful spots. Keep in mind that a client who’s rolling his quads for the first time may be sensitive everywhere.

Stay above the knee joint, and roll as far up the thigh as possible.

IT band

Now we get to the dreaded iliotibial band. When it’s tight, the IT band can prevent the kneecap from tracking properly, and that can create pain on the inside or outside of the knee.

Even though the client is rolling on the outside part of the leg, he’ll still need to rotate a little to find the problem spots. (Although, like the quads, the entire IT band can light up the first few times a client rolls on it.) Rolling forward a bit onto the quad can help separate the quad and IT band, which need to work independently but can sometimes get “stuck” to each other.

The range of motion here is important: You don’t want the client to roll over his knee or the greater trochanter, the bone on the outside of the leg at about groin level. There’s no benefit to putting pressure on it, and if the client has any amount of hip bursitis, it’ll be the wrong kind of painful.

Step 2: Ankle mobility drills

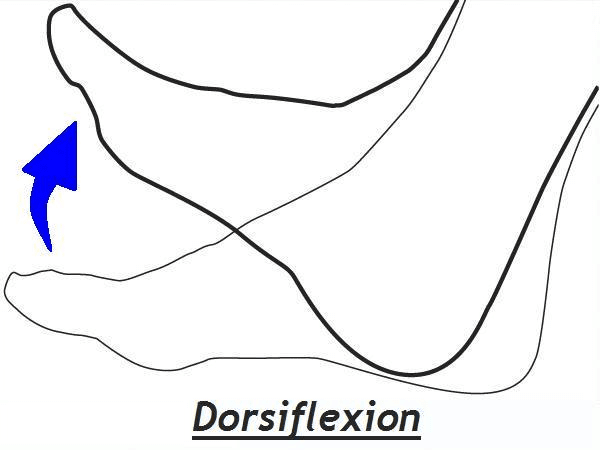

“Dorsiflexion” is one of those terms you probably stumbled on the first time you saw it in a textbook. The way it’s normally illustrated is like this, with the heel on the ground and the toes lifted up toward the shin:

But functionally, dorsiflexion is most often achieved with the toes on the ground and the lower leg moving forward over the ankle and foot while running and walking. And it’s the loss of this type of dorsiflexion that causes knee problems.

It typically happens one of two ways: prolonged inactivity, or too much activity with flawed movement patterns.

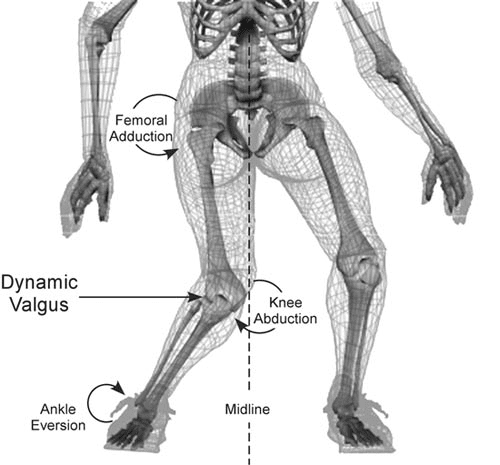

When the shin doesn’t move forward over the ankle, it shifts inward. This ankle eversion causes the arch to flatten and the knee to go into valgus, collapsing in toward the other knee.

If you do this long enough—and it takes some time before you start to feel pain (usually on the medial part of the knee joint)—your brain starts to treat ankle eversion and knee valgus as your normal movement pattern. At that point, even if you correct your ankle mobility, your knee and ankle will still collapse inward.

Improving your walking and running mechanics is beyond our scope here. So let’s focus on ankle mobility.

Step 3: Hip-dominant exercises

When the glutes and other hip muscles are weak, the hip doesn’t stabilize properly. That allows the femur to adduct, which produces knee valgus—the same motion you see when the ankle is limited. So if your client has glute weakness and ankle mobility issues, your work is cut out for you.

The four exercises I show here—glute bridge from a box, band walk, kettlebell deadlift from a box, and Romanian deadlift—are some of my favorites. But we all know many others that could work just as well, if not better, with individual clients.

Use your own judgment on sets and reps. How you do these exercises very much matters. Even when your clients can do them pain-free, you still need to focus on motor control.

That’s especially true of the deadlift variations, on which you probably want to use lower reps.

The band walk tends to be self-limiting, in that you’ll be able to see when fatigue sets in and the client’s form breaks down. And with glute bridges, you can typically do high-rep sets without any problems.

READ ALSO: Training the Hip Hinge

Glute bridge from a box

Use a box or bench that’s about 12 to 14 inches high, and make sure your client sets up with his shoulder blades at the edge of the box.

Get your client to finish the movement in table-top position, with his torso and thighs parallel to the floor. Squeeze the glutes hard at the top of the movement, and then control the descent. The glutes may or may not touch the floor between reps. It’s fine either way, as long as the glutes fully contract at the top, without any of the work shifting to the quads or hamstrings.

READ ALSO: How to Train Clients Who Have Back Pain

Band walk

Most of the time, when you do band walks with your clients, you coach them not to lean to the side. You want the torso to stay perpendicular to the floor and the client to remain in an athletic position.

These are different. Starting with the feet about hip-width apart, have the client abduct her left leg while leaning to the right and squeezing the right glute. Don’t let her swing the leg out or fall over onto the lead leg; make it a controlled movement out and back.

As you can see in the video, you’re traveling just a few inches on each step. The lead leg should return most of the way to the starting position by the time it lands.

Both hips will fatigue, so you probably want to let your client rest briefly before switching sides.

Kettlebell deadlift from a box

Make sure the kettlebell touches the box in the bottom position, and have your client pause there briefly, but don’t let her relax. The key to this exercise is to maintain total-body tension throughout the movement.

Romanian deadlift

The RDL is, essentially, the top half of the deadlift. But because you start from the top rather than the bottom, the muscle-coordination strategy will be a little different from the previous exercise.

Make sure the movement comes from the hips. You want the client to start with a slight knee bend, and maintain that same knee bend throughout the range of motion.

READ ALSO: Troubleshooting the Deadlift

Step 4: Deloaded knee-dominant exercises

When your client consistently reports little to no knee pain in her everyday life, it’s time to put knee-dominant movements like squats and lunges back into the program.

Your best strategy is to deload the exercises by using bands or pulleys for assistance. That puts less demand on the muscles and joints and gives you a chance to fix movement impairments like ankle eversion and knee valgus.

I typically have my clients do just two to six reps per set at first, using as much or as little assistance as the client needs. The goal isn’t to get a great leg pump; it’s to do each exercise pain-free and with good form.

If a client normally feels knee pain when he does squats or lunges, but none when he deloads the movements, it suggests the pain results from muscle weakness or mechanical issues, rather than a problem with the knee itself.

Practice it on your own a few times before trying it with a client; that way you’ll get a sense of how much assistance a client might need to descend slowly and pull up from the bottom position, all without pain.

READ ALSO: Why People Must Squat Differently

Deloaded squat

You can do this with a cable machine, as shown, or with a band, as I show here.

Deloaded lunge

Again, you can try this with a cable or band.

Final thoughts

The longer a client has had chronic knee pain, the more muscle, movement, and lifestyle issues you’ll have to confront.

That’s why patience is the final part of the puzzle.

Sometimes you can get fast results by fixing a flawed movement pattern. Sometimes you get steady progress by helping a client build strength in key muscles while learning how to squat or lunge properly. And sometimes it’s a long, frustrating process in which weeks of training can be undone when the client slips in the shower or stumbles down a step.

You can’t change what the client did in the past. But with these strategies, you can help the client achieve a pain-free future.