According to the 2012 census, there are currently 43 million adults who are 65 or older, with the numbers projected to reach 70 million by 2030. That’s a large pool of potential personal training clients for you! That initially seems like a jackpot, but you should first arm yourself with special training considerations for this population. Here’s what you need to know.

In this article, we will go over some simple functional assessments for your older, potential client, but let’s make sure we’re all on the same page about how the aging process works.

ALSO READ: Quickly Screen and Assess a Client’s Mobility With Two Simple Exercises

Aging makes strength training that much more important.

First, age changes various structures and numerous systems within the body, and your approach to strength training needs to adapt to these changes.

In a study published in Disability and Rehabilitation, people in their 80s have 40 percent less strength than people in their 20s. That’s to be expected, because studies on our physiology have shown that our maximal strength capacity reaches a peak sometime around the second or third decade of life. By the fifth decade, however, we begin to see a gradual decline.

In fact, research has shown that skeletal muscles, in particular type II fibers, change with age. These type II fibers both decrease in size and atrophy over time, which means their strength decreases as people get older. Not surprisingly, aging does not do someone’s strength and muscle size any favors; and it’s this decline in muscle and strength that is strongly associated with increased risks of falls and physical disability in older adults.

That’s where we come in.

If we help them work on leg strength (particularly in hamstrings and gluteus maximus) and gait mechanics, we can help them reduce the risk of falls and improve their quality of life. That’s because strength training improves strength of bones, connective tissue, and the size of fast and slow-twitch fibers. It also reduces blood pressure and improves blood flow, and those are just a few benefits.

Bottom line, we know strength training matters, but they may not be interested in bigger muscles. To put this in terms that matter to them, we need to focus on helping these aging clients regain their quality of life. We need to help them get up and get down without assistance. Or better yet, we need to get them to the point where they continue to have the strength and energy to do the everyday things that bring them joy, like playing with their grandchildren.

Before starting them on a program, use these functional assessments.

When you first take in an older client, you must keep these physiological processes and barriers in mind. The process will differ from person to person. We want to use a variety of tests to assess the client’s physical capabilities before going any further.

Start with balancing tests.

Maintaining balance involves a complex interaction among the sensory, vestibular, and visual systems. We already know that aging reduces muscle strength, but it also impacts reaction time.

Assessing an older client’s balance needs to be objective and not guesswork. While there are many tests available, few are objective, measurable, and supported by research. However, I’ve found the following to be adequate for our needs:

1. Timed “up and go” test

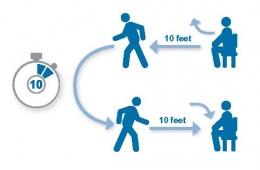

Use a standard armchair and indicate an imaginary finish line that is located 10 feet from the chair.

The objective is to have the client get up, walk as quickly as possible to the line, and back to the chair to sit down again. You are tracking and later assigning a score to the time it takes (in seconds) for your client to complete the task.

Encourage your client to wear regular footwear and to use their customary walking aids, if any. You are not to provide any physical assistance.

Scoring:

* Less than 10 seconds to complete means the person has a low risk of falling.

* Over 20 seconds to complete means the person has a high risk of falling.

2. Sit-to-stand test

This test mimics an everyday activity: can your client comfortably get in and out of her chair?

During this test, have the client sit with her back touching the back of the chair. Now ask the client to stand from the seated position, counting aloud every rep. Stop the test when the patient can get five reps of sit-to-stands.

Scoring: age norms

* Age 60-69: 11.4 seconds

* Age 70-79: 12.6 seconds

* Age 80-89: 14.8 seconds

3. Functional squat test

When your client is picking up or moving something, she is squatting, one of the most fundamental primal movement patterns that everyone does on a daily basis. Properly performing the movement requires good ankle and hip mobility, while also demanding stability in the knee and lumbar spine. Understanding the functional anatomy and muscle recruitment is fundamental when prescribing this exercise with any client.

When analyzing the movement, watch the descent.

* The hip flexors should concentrically contract with slight lumbar flexion.

* While the knees undergo flexion, the gluteus maximus and hamstrings eccentrically contract.

* At the ankle, dorsiflexion occurs, where the anterior tibialis concentrically contracts and the gastrocnemius eccentrically contracts.

When returning to an upright position, the opposite occurs:

* The hip flexors eccentrically contract, a slight lumbar extension is present, and the knee transitions from flexion to extension.

* Hip extension occurs via the gluteus maximus while the hamstrings concentrically contract.

* Ankle plantar flexion occurs with the concentric contraction of the gastrocnemius while the anterior tibialis eccentrically contracts.

All of these tests together should help inform your programming for the older client.

Focus on these muscles in your older clients.

It is important to understand the muscles behind your client’s everyday movements. Large muscle groups, including shoulders, arms, trunk, hips and legs, are susceptible to the aging process. The client’s training should target these muscle groups.

To list a few examples: the latissimus dorsi muscle assists with sit to stand; the gluteus maximus is a primary hip extensor muscle involved in walking and climbing stairs; the hamstring muscles flex the knee and extend the hip for everyday activities such as walking, sit-to-stand movements, and going up stairs. Further, glute medius and minimus muscles help them get in and out of bed, a car, or even a bathtub.

Aging is inevitable, but many of the physiological declines can be mitigated and falls can be prevented. One of the keys to helping them is arming yourself, their personal trainer, with more knowledge about the aging client’s body. Help your client age gracefully with an appropriate intervention program that consists of strength, endurance, and balance training.

Photo Credit: All images in this article by Stock Unlimited Images