A client getting injured is every trainer’s nightmare.

A client getting injured is every trainer’s nightmare.

The risk goes up considerably when you’re training clients online, because you can’t physically be there to supervise. You have to trust that they won’t break form on their exercises or push too hard.

But don’t lose sleep over it. Strength training is still one of the safest physical activities a person can do.

A 2017 review in Sports Medicine concluded that rates of sports injuries from all kinds of weight-training (bodybuilding, CrossFit, strongman training, etc.) were relatively low compared to team sports, and that bodybuilding training had the lowest injury risk of all the types of lifting—just one injury for every 1,000 hours of training, on average.

(To give some perspective, the injury risk for the same amount of long-distance running is eight times higher among recreational runners.)

Most personal training clients follow bodybuilding-oriented routines—think machines, isolation exercises, and other methods geared toward muscle growth (as opposed to maximum strength, power, speed, or endurance)—so if something does go wrong, your clients aren’t likely to suffer serious damage.

But with all that said, you still want to ensure that their training is as safe as possible, and to help you, I can offer a few guidelines.

How to ensure your online clients perform exercises correctly and safely: A four-part plan

1. Be as present as possible.

You can always keep your eye on an online client—even if they live in another town, time zone, or country.

Have them take you with them to the gym via their smartphone or a Zoom call so you can watch them train.

If they train in a public facility, they may have to get their gym’s permission to carry their phone around and converse with you during the workout, but with today’s technology, there’s no reason you shouldn’t be able to monitor their training live and in person (albeit remotely).

No, I don’t think it’s necessary or practical to do so for every workout, but it’s important for brand-new clients who have little-to-no training experience, and whenever you assign them a new array of exercises.

At the very least, get the client to video themselves doing the exercises and send you the video right afterward to critique.

Option B is to find a local trainer and cut them in on the action.

Say, “I have this client, Susie, who lives in your area, and she wants to buy a session with you to make sure she’s performing the exercises right.”

You design the workouts, and the trainer makes sure they’re performing the exercises safely.

Note that this is also the more expensive option, as your client is already paying for your coaching and now needs to pay for a session with another trainer on top of it.

On the other hand, hiring a trainer has some big advantages. For one thing, it ensures better care for your client because they have somebody to work with in person (freeing you up to do other things).

For another, it expands your network. Now you know a (hopefully) good trainer in a new town, with whom you can exchange ideas and, possibly, more clients.

2. Explain the difference between soreness and pain.

Clients who are beginners often can’t clearly distinguish between the normal delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) that results from a workout and the pain that comes from actual injury.

If they’re not sure of the difference, they may think they have to keep pushing hard when their body is really telling them to stop.

Before you start training them, explain that a certain degree of soreness is okay, but pain is bad.

DOMS is a dull sensation that they’ll feel over a broad area, and it usually goes away within 72 hours. (If it lasts longer than that, you may need to scale back your workouts.)

Pain is usually sharp, and concentrated to one specific area. If the client retraces their steps, they can probably figure out what exercise or point in the workout they started feeling it, and you can make adjustments from there.

3. Use the RPE scale to determine load.

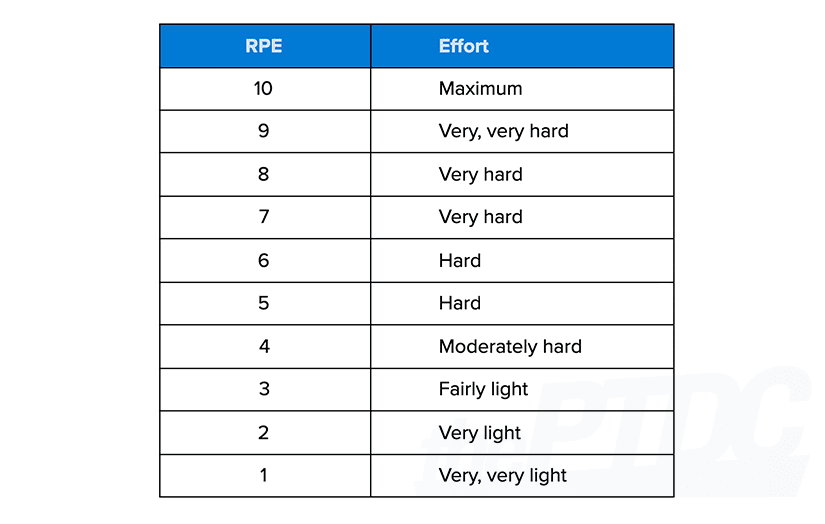

RPE stands for rate of perceived exertion. It’s a subjective measure of how hard a set feels to perform, and it can help your clients determine how hard you want them to train, and how much weight to use on their exercises.

If they know when to push hard, when to hold back, and how much to lift, they have a better chance of getting the training effect you want while minimizing the risk of injury and overtraining.

RPE for strength training was popularized by Mike Tuchscherer, founder of Reactive Training Systems. You can read several articles about it on Mike’s site, but basically, you use numbers to guide the intensity of effort.

A 10 on the RPE scale represents going all out, performing a set until you can’t get another rep.

For example, assigning the client a set of 8 reps at an RPE 10 means they should do 8 reps with a weight that allows them only 8 reps—so that a ninth would be impossible with good form.

An RPE 9 might allow them one more rep than the prescribed number; an RPE 8 might let them get two more reps, and so on down the scale.

Most of your workouts will probably call for RPEs in the 7 or 8 range, so the client uses challenging loads, but doesn’t push so hard that they risk breaking form or burning out.

RPE allows you to customize workouts on the fly.

Say the person has to do 8 reps at an RPE 8, which means they should choose a weight that they can do 10 reps with but stop at 8. If the person gets 8, but it feels so hard they know they couldn’t have gotten a ninth rep, they now know that the load was too heavy, and they should reduce the weight by five or 10 pounds for the next set, or the next workout.

With a little practice, anyone can use RPE to get more out of their workouts.

4. Track recovery

Sometimes doing an exercise safely and correctly comes down to how you’re spending the 23 hours of the day that you’re not in the gym.

You have to make sure your clients are recovering from their workouts.

Ask about what they’re eating, how they’re sleeping, how sore they are from workout to workout, and how they’re progressing week to week.

Something is amiss if they tell you:

- They don’t sleep well on a regular basis.

- They’re constantly sore.

- They aren’t able to add weight or reps to their exercises.

- They feel mentally sluggish in the gym.

They’re either overtraining or under-recovering. Find out what it is and correct it.

What seems like the smallest tweak can make a big difference in how they perform, and the kind of results they get long-term.

Learn more: Get answers to more online trainer questions.