The following is a guest contribution from Anoop Balanchandran that originally ran on his site exercisebiology.com. It is re-edited and republished here with permission.

Pain is a topic that fitness professionals must have a better understanding about. In this guide to pain I describe what pain is and have included a few questions that I feel everybody, including trainers, might have trouble with.

Is Pain in the Brain?

What is this whole talk about how injury and pain are not related and how pain is in the brain? Is it true? If so, I don't get it.

We used to believe (some people still do) pain and injury to be highly correlated and would utilize the measure of pain as an indicator of tissue damage. Unfortunately, as we begin to learn more about pain and injury, it is clear that pain is not an accurate indicator of injury nor damage. To understand this better, we have to understand a very important concept:

Pain does not (technically) begin at the level of the tissues: While we once thought pain to originate at the level of the tissue (and that "pain" information was carried up to the brain), we now understand that these carriers, nociceptors, relay "danger" information to the brain for processing.

Once the "danger" information reaches the brain, it is then up to the brain to decide whether these signals are dangerous enough to respond by producing an output of pain. So we don't have pain receptors or ascending pain pathways as we commonly thought. Pain doesn't begin until the brain determines it is needed.

This response is quite individual. One may have a very serious injury and complain of little to no pain, while another may have a very minor injury and experience extreme pain. The degree of injury is not always related to the degree of pain. Hence they say, injury and pain are not related and 'pain is in the brain'.

What Influences the Brain's Decisions?

But what makes the brain think it is indeed threatening or I am in danger, and let's generate some pain?

Well, many things, actually. Your attitudes, beliefs, past experiences, knowledge, social context, sensory cues, nociception and so forth may all be confounding variables influencing your brains decision. What we have to understand is nociception is just only one of many inputs that the brain asses to see if it is indeed in danger. Pain is only generated if the brain concludes that body is in danger and action is required.

If a Hand Gets Cut in the Woods, Does it Still Feel Pain?

Are you telling me if I cut my hand, I won't feel pain? .

A lot of people who are resistant to accepting this concept may only be considering examples where they had injury and then felt pain. A=B.

Unfortunately, this relationship isn't as clear as we may think. We may be subconsciously ignoring the countless times where we had an injury and felt no pain (or pain not proportional to the extent the injury). We have experienced plenty of bruises and cuts, with little clue on how or when it happened.

Forget the tiny bruises and cuts. It is well known that around 40% of the people admitted to the emergency room with horrific wounds have no pain or low pain even after long delays (1). And mind you, these people are alert, rational and coherent ('not in shock' as most people tend to believe). If a crowbar is sticking through your neck or an amputed arm doesn't result in pain, why on earth would we think injury is an accurate indicator of pain?

So how could these horrific injuries result in NO pain? As we learned, nocicepetors relay danger signals, and it is ultimately up to the brain to produce an output. Most often these horrific injuries happened in a context where survival of the person was at stake, which is a lot more threatening than the injury (ie. focus on the injury or sustain life).

And as time goes by and the brain concludes that you are out of danger, it now focuses back on your amputated arm. I cannot work, I cannot lift my kids, I know and have seen amputees struggle, I can see the blood on the bandage: All these beliefs and attitudes and sensory cues are only heightening the fear or threat level of the injury in the brain which results in pain.

Now what if your thoughts/attitudes were more positive or less threatening? In 1950 Henry Beecher did a similar study. They wanted to see why soldiers who got injured in war took much less morphine than a civilian or why they had much less pain that expected.

The results indicated that it is simply because of "meaning". For a solder, despite experiencing a major injury or an amputation, he still survived a war , and could return home and be with his family and friends. The soldiers beliefs and attitude was likely influential over the brains defensiveness, resulting in much less pain than expected (2).

And mind you, these things are happening in a split second and it is outside our conscious control.

Are Phantoms Real?

If the brain sends an output of pain, and nociception is just one of the inputs, can we have pain without nociception?

Yes.

A classic example is phantom limb pain, which has puzzled us for years. In phantom limb pain, forget damage and nociception; people no longer have a body part, yet still feel pain (in their missing body part). Phantom limb pain is a remarkable example of how pain occurs with absence of nociception. We also see plenty of examples around us where people experience pain with no damage or injury.

Now how do researchers study these questions? Here are two popular studies:

Study 1: The participants in this the study were touched by a cold piece of metal (-20) to evoke a nociceptive response. They were also visually shown one of two colored lights, either red and blue. Before being touched, it was explained that the light was very related to the cold stimulus.

Now what did they find? Although the stimulus was identical, 8 out of 10 subjects felt more pan when the red light was shown than blue light. If you think about it, we have learned that red always signals danger. Though there were individual variations, it was very clear that the color of the light changed pain, but not nociception. The nociceptve fibers evoked the same response (as seen by C & A delta fiber activity) under both conditions, but the pain dramatically differed. (3)

Study 2: Here the subjects placed their head in a sham or fake stimulator and were told a current would run through their head. They were told that the pain will increase as the intensity of the stimulation goes up. As expected, the pain went up as the stimulation went up even though there was no stimulation to begin with. This is another fascinating example of pain without nociception. (4)

What About Chronic Pain?

I have chronic low back pain for years due to the 2 herniated discs as shown in my MRI. How does all this brain talk ever change the treatment of chronic pain?

Since this guide to pain has now described the biology of pain, it is a good time to talk about pain management. As you rightly pointed out, acute pain is pretty straight forward and well understood. As the name implies, it is just acute or short term. We get injured, we 'may' feel pain, healing takes over, pain goes away, and we are back to normal (usually 3-6 months). Nobody is really bothered about acute pain, what everyone is worried about is chronic pain.

Chronic pain has always been a mystery. Why should this pain last for years and years when injury had enough time to heal? Multiple bullet wounds and major amputations heal within months so why should this tiny injury to your knee or shoulder last for years and years?

Or how come there are large number of people who have the same dysfunctional tissue but have no pain? We know that around 40% of the population have disc herniations but have no pain whatsoever. And guess what, these people do not end up in pain years later either. This is the exact reason why the American College of Physicians have come forward with clinical guidelines saying" Clinicians should not routinely obtain imaging or other diagnostic tests in patients with nonspecific low back pain".

We now clearly know that abnormal findings on the x-ray and MRI (like disc herniations, bulging disk, degenerating joints and so on) are clearly NOT related to the onset, severity, prognosis, or duration of low back pain. If 40% of the general population do have disc hernataions, I do suspect everyone who lifts weights will have one or two disc herniations. (5) (6)

Before we understood the role of brain in pain, we always thought that pain is an accurate indicator of damage and nociception equals pain. So chronic pain always meant that there is an injury yet to be healed. Hence all our treatments were focused on fixing tissue damage and dysfunctions (the biomechanical model). But now we know that in chronic pain, the injury has healed long back and what is maintaining the pain is the sensitive nervous system and the brain. Or in other words, the brain still thinks there is threat and hence still outputs pain.

Does Your Ouchy Hurt to Touch?

What do you mean by a sensitized nervous system?

Remember the last time you had a cut or a contusion? Not just the damaged area, but even the surrounding area was painful even to the slightest of touch (defined as hyperalegisa and alloydynia).What we see here is an increased sensitivity of the nervous system. In other words, both the threshold for activation of the nociceptors is lowered AND the response of the nociceptors is increased. Remember that muscles, joints, skin are just the hardware, the nervous system is the software and where all the action happens.

In chronic pain, this nervous system sensitivity is still maintained. The brain believes there is a threat and sends an output of pain. So just flexing your low back with a small weight, which seemed pretty harmless, is now threatening enough to evoke pain.

The simple goal of any pain treatment is to lower the sensitivity of the nervous system (includes brain).

Top Down or Bottom Up?

I see. And how do you lower this sensitivity?

Two ways:

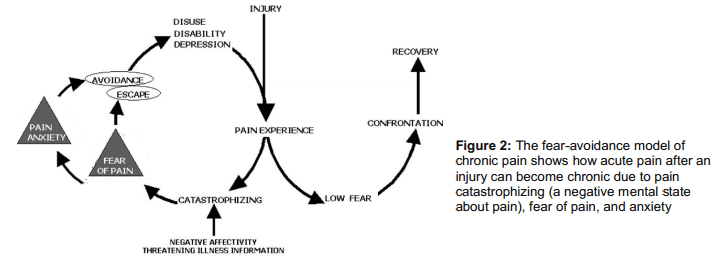

The Top Down Approach means changing your attitude, beliefs, knowledge (neurophysiology of pain) about your pain and in turn, lowering the threat value of pain. People get hurt, they experience pain, healing follows, and they recover. But in some folks the pain lasts forever. And why is that? According to one of the most well-accepted models - the fear-avoidance belief model - people who have heightened fear of re-injury and pain are good candidates for chronic pain.

Lack of knowledge or incorrect knowledge, beliefs ( hurt always means harm, my pain will increase with any activity and so forth), provocative diagnostic language and terminologies used by medical therapists like herniated disc, trigger points, muscle imbalance, and failed treatments can further heighten this fear or threat.

Education to lower the threat is THE therapy here. We now have some very good evidence to show that just pain physiology education or the top-down approach is enough to lower pain and improve function. (7)

The Bottom Up approach is what we see around us: surgery, postural fixing, trigger point, muscle imbalance, movement re-education, manual therapy, acupuncture and the list keeps growing. Almost all treatments out there are trying to lower the nociceptive drive without much consideration to the top-down approach. This is solely because these treatments are based on the outdated model of pain.

We now suspect that positive effects of manual therapy may be due to neural mechanisms than the tissue and joint pathology explanations that is often offered. So even the bottom up approach is working via de-sensitizing the nervous system. Although not intended, there are top-down mechanisms clearly at work even in bottom up approaches (like the placebo effect, a credible explanatory model, the belief in the therapist).

What's needed is a combined approach that takes into account the "entire individual" and that's where the biopysycosocial model of pain treatments walks in. The biopsychosocial model addresses the biology (nerves, muscle, joints), psychological (beliefs, thoughts, fear) and social aspects (work, culture, & knowledge).

What's Wrong With the Current Methods?

So what is wrong some of the current treatments which are based on the old biomechanical model of pain?

Many popular methods place an over-emphasis on the bottom-up approach assuming tissue damage and nociception as the sole driver of pain.The is called the 'find and fix it' model.

Many popular methods place an over-emphasis on the bottom-up approach assuming tissue damage and nociception as the sole driver of pain.The is called the 'find and fix it' model.

A good question is if it is working, should we worry about all this brain talk?

It is estimated that 1 in 4 people in America are in chronic pain and this was 1 in 7 in the 90's. These numbers tell us that the current approach is not working (even if we thought it was). Furthermore, none of our treatments show any specific effects. That means for low back pain: manual therapy, acupuncture, general exercise all seem to elicit similar effects. (8)

What is disconcerting is these treatments are given in a context that there is something wrong with the tissues and we need to avoid/prevent/fix it. This structural pathology approach is great to raise the threat level in the brain and in turn maintain or worsen your pain. So even if you get pain relief, you maybe nicely setting yourself up for some future pain problems.

Should I Stop and Change Everything That I'm Doing?

Now I am confused. Should I tell people not to use an arched back when they lift because it can raise the threat in the brain? Should I stop foam rolling and other injury prevention methods?

Nope. Just like I wouldn't advise anyone to cross the street with their eyes closed, I wouldn't advise anyone to pick a 200 lbs barbell with a rounded back. The age-old simple advice of avoiding extreme loading at the end range of motion still holds good. So proper form is always recommended.

What we don't want to do is overemphasize or exaggerate our case for injury and pain prevention. Some common examples are: Asking someone to sit with 20% tension in abs, always be upright and never slump, educating disc herniation as the end of the world, knees should never go past toes, spinal rotation is bad and so forth.

If you don't have any clear evidence and you are just speculating, and most are speculation, it is better to clip that ego and avoid the talk. You can do lot more harm than good.

Should you stop foam rolling and other injury prevention techniques?

This is a good question, but a better question to ask is do these really prevent injuries in the first place? Most of the stuff that you often hear are just 'claims'. If you think those really help, you have sufficient evidence and the client have injury concerns, then go ahead and do it. But what we have to be careful is the language we use to explain these techniques. For example, a better way to present foam rolling is to improve mobility and blood circulation instead of another tool to exorcise out those evil trigger points.

Can Pain be Prevented?

Pain is a protective mechanism. If we didn't have pain, we would be all dead. So pain is normal and necessary. Acute low back pain is as harmless as a common cold and is unavoidable in your life.

Second, what we need to worry about is pain that can become persistent or pain that sustains even after the tissue is healed. And the best way to prevent pain chronicity is to have a better knowledge of pain physiology and how pain is an output of the brain rather than a simple response to injury.

It has been shown that people report less pain and less frequently after they receive pan education. Why? Simply because you have lowered the threat level in your brain. Pain education may also serve to lower the pain intensity with acute injuries. So throw away all those unnecessary fears and beliefs about pain and injury.

What About Posture?

Almost all treatment modalities out there to explain chronic pain are based on the structure-pathology model. We have been studying and researching posture for more than 30 years and we still don't have any evidence to show posture causes pain. In fact, we have very good evidence to show that posture is not correlated with pain. And If you have been keeping up with me so far, it is not so surprising. Is it?

What we have to understand is that pain is just one part of a complex stress response. If you get inured, the body responds by releasing adrenaline, activating large muscle groups to evade threat, deactivating small postural and stabilizing muscles, changing your gait or posture to further avoid injury, slowing digestion, triggering swelling and inflammation and so forth.

All makes perfect sense since the body wants to protect and escape from further threat or injury. Once the pain becomes chronic or threat becomes chronic, these complex protective responses are also maintained. You will still maintain those anatalgic or pain evasive postures, your core or postural muscles are still less activated, the over active muscles tend to shorten and become prone to trigger points, and the swelling and inflammation becomes wide spread.

Most of the aforementioned responses that are often blamed for the cause of our pain are just the consequences of a well-designed, threat response system - posture just happened to be one of them.

There is a time and place for postural correction but I just mainly do it to improve aesthetics and function

Are Weak or Uninhibited Muscles the Problem?

What about strengthening muscles to relieve pain. I thought weak muscles were the problem.

Strengthening muscles may or may not have much of an impact on pain. What strengthening is good for is to raise the tissues tolerance so the affected area doesn't get re-injured.

The pain relief people obtain when they do exercises could be explained by the non-specific effects of exercise. For example, you have managed to convince and comfort your client that movement is good and not to be feared, especially the body part in question. You also educated them that pain is due to weak or imbalanced muscles and will soon resolve.

The improvement in blood flow, performing the actual movement (which was supposedly harmful), the self-belief that he or she will get better all contributes to lowering the threat value in the brain. If you care to notice, these top and bottom up approaches are common to all movement or exercise based treatments. What is not common is the unique mechanism offered as the rationale for these treatments and their ignorance of the powerful non-specific effects of their treatment.

Once again, although the pain may resolve, we have used an explanatory model that is further instilling the belief that is pain is due to tissue pathology or tissue dysfunction or weakness. And that my friend is not good.

I think that's all I have. I have omitted a few things, like the pain signature and other pain mechanisms which is bit more complex. I expect (and hope) this article has raised enough curiosity in you to question some of your own beliefs and understanding about pain and injury.

Please do share this article to everyone you know. It is probably one of the most important articles I ever wrote, and that you will ever read.

Here Are Some Great Sites to Read More About Pain

www.forwardthinkingpt.com

www.bboyscience.com/

www.saveyourself.ca

www.bettermovement.org

Here's a Book List

Beginner Level

Explain Pain - Butler & Moseley (This is a must read)

Painful Yarns - Lorimer Moseley

Intermediate Level

Pain - Patrick Wall

The Challenge of Pain - Ronald Melzack

Sensitive Nervous System - David Butler

The Back Pain Revolution - Gordon Waddell

Topical Issues in Pain - Louis Gifford

Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching patients about Pain - Adriaan Louw (a book on how to do the top down approach)

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Jason Silvernail DPT, DSc, FAAOMPT and Joseph Brence, PT, DPT, FAAOMPT, COMT, DACc for helping me edit the article. Special thanks to Joe for painstakingly going through the article and making sure everything I wrote is accurate and consistent with the pain science. Please do bookmark his excellent website: www.forwardthinkingPT.com

References

(1) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7145438

(2) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13345630

(3) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17449180

(4) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2038488

(5) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2312537

(6) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16946663

(7) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22133255

(8) http://www.amazon.com/Wall-Melzacks-Textbook-Pain-Consult/dp/0702040592